As the machine of war ground tens of thousands of Canadian lives to dust overseas, a lesser-known contingent of volunteers prepared for invasion by air or by sea in remote coastal communities in B.C. They were called the Pacific Coast Militia Rangers (PCMR).

Their history is hidden compared to other Canadian military units. Library and Archives Canada, where most of Canada’s military unit and personnel records such as diaries and photographs can be found, doesn’t contain any PCMR records.

“It’s a significant part of history on the Sunshine Coast. Most people think of the war, the volunteers going oversees or to some other part of Canada, but these rangers stayed here,” said Stu McDonald from his home overlooking Georgia Strait. “There’s a lot of relatively unknown stories of the coast of B.C. during the Second War.”

The mysteries are driving the retired Gibsons-based history teacher and major-general to unearth artifacts and stories – enough, McDonald hopes, for a public exhibit on the Sunshine Coast. He has devoted nearly two decades to this project.

Lottie and Bruce Campbell of Gibsons remember the PCMR. Her father, 6-2 with deep strength, Norwegian features, blue eyes and curly light hair, was one of the Rangers. “He was a very sociable, happy person,” said Lottie from her home outside Gibsons. “He was everyone’s friend.”

George Bernard Hostland was a hard-working father of four, a talented singer and tap dancer. He yearned to fight overseas, but his specialized knowledge in the forest industry kept him at his home in Port Mellon working at Sorg Pulp as a pipefitter – not his first choice. “My mother was very happy and my father was quite disgruntled,” Lottie said.

Staying at home was a fate common to Coast families during the war. People who worked in protected occupations in fishing or forestry were disqualified from overseas service. But their local knowledge made them invaluable to the military. “The Rangers would know a great deal more about the landscape and the geography on the Sunshine Coast and the inlets and rivers than anybody in the regular reserve army would know,” said McDonald, who said they would have served as guides for the regular army.

About 15,000 people served as PCMR in B.C. and McDonald estimates up to 100 of them were embedded in Coast communities from Port Mellon to Pender Harbour. But so far, he has tracked down with certainty only the names of the leaders of the two units on the Coast, PCMR Company No. 40 based in Sechelt and covering Halfmoon Bay and Pender Harbour, and Company No. 42, covering Roberts Creek and Gibson’s Landing. Both units were formed in 1942. Capt. B.H. Harrison and Capt. Ernest W. Parr-Pearson led Sechelt while Capt. R.T. French and Capt. A. Pilling led the Gibsons-based company.

The name Parr-Pearson also surfaced at a recent exhibit at the Sechelt Arts Festival, which McDonald happened upon while volunteering. “It was pretty exciting,” he said of the chance discovery. “I’m hoping the Parr-Pearson family might have some additional information.” A few materials in the Sechelt archives show he founded Coast News, which he ran on Wharf Street, and that he lived in Sechelt. His daughter, Diane Benner, recalled that he was a respected public figure and businessman, but her memories of him were cut short after he died of a brain aneurysm when she was 18.

That loss speaks to another kind of urgency for McDonald. With the Second World War a lifetime away, the chance of getting first-hand accounts is diminishing. “There’s a slim chance that some of them are still alive,” he said. And since the units didn’t engage in direct military warfare, there are fewer records to go by.

The Rangers may not have fought in the war, but according to McDonald, the purpose they served was critical, and the threat of invasion was palpable.

“For people living on the coast, there was dramatic increase in concern as a result of the Japanese Navy’s presence in the Pacific,” McDonald said. On June 20, 1942, Japanese submarine I-26 shelled a lighthouse at Estevan Point on the west coast of Vancouver Island – the first enemy attack in Canada since the 1800s. The same group of submarines operated off the coast of the Pacific Northwest. The Rangers acted as the first line of defence against Japanese invasion.

Lottie Campbell was around nine years old in 1942. She remembers the blackouts, when communities were required to dim their lights at night to protect against aerial attacks. “We were really very aware of it, but we never heard bombs and never heard planes,” she said. The shelling at Estevan Point gave her husband another feeling. “That was frightening, but it was more frightening to adults than us as children,” he said.

Were the Japanese air force or navy to attack, they would have been up against small Ranger units with no age limit. “As long as you were capable of finding your way through the woods, running a boat or leading people in territory unfamiliar to them, then it didn’t really matter what age you were, you were eligible to join and serve,” McDonald said.

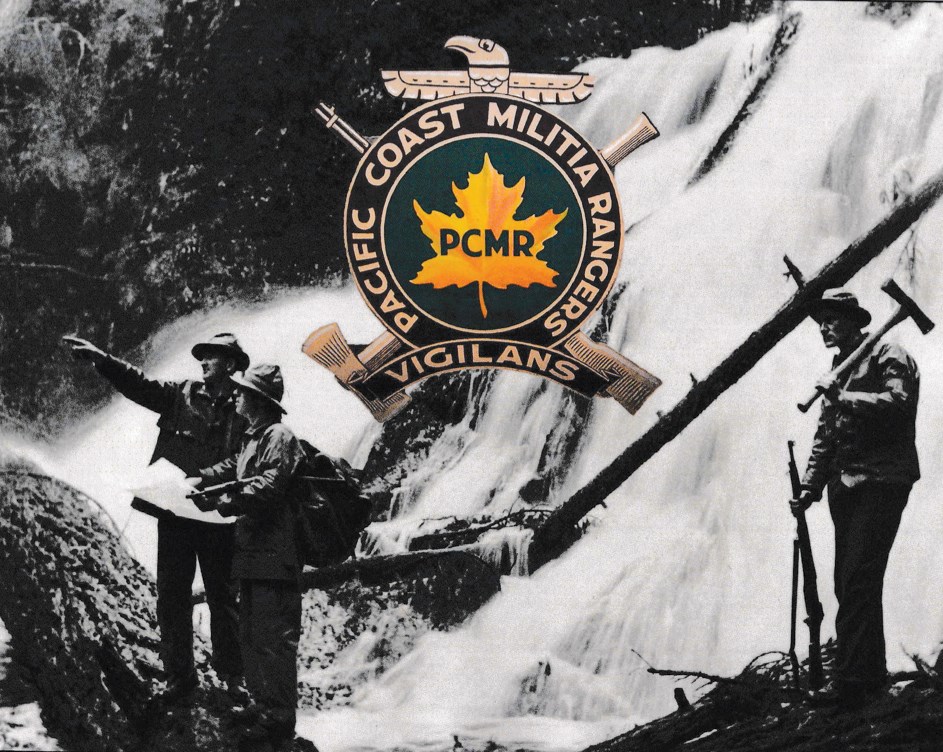

Uniforms were reminiscent of logging clothing made of waxed canvas, a “unique floppy bush hat” to keep the rain off, an armband identifying their non-civilian status, and the relatively rare cap badge. Part of its insignia is a thunderbird looking out to sea – the only First Nations design element on any Canadian cap badge that McDonald is aware of.

Details about training are few. “They were all sworn to secrecy. So probably, when they went home at the end of their training night in Gibsons or Sechelt or Powell River, they probably didn’t say much to their family about this,” McDonald said.

He said they likely knew how to defend themselves against larger military forces, how to identify Japanese aircraft and tanks, and defence against tanks and aircraft and surveillance. “And they would also have been excellent, as we call them now, guerrilla troops, because they would have been able to survive for days in the woods of British Columbia,” McDonald said.

Rangers were also trained to fire weapons and in exchange for their volunteer service – they were only paid when on active duty – they could keep their rifles for $5 at the end of the war. “That was a pretty inexpensive proposition for the government of Canada,” McDonald said.

Only one short passage in a book co-authored by local poet Peter Trower reveals what training would have looked like. It was a memory Bruce Campbell had, which Trower transcribed.

“They had a lot of guys up there who had never seen a weapon before and they came to Hillside to practise,” reads the passage. “It was unbelievable – they sprayed lead all over the country! They had these sten guns – the Plumber’s Dream – or whatever they were; they were just cheap things but they would go through 33 rounds with just a pull of the trigger,” Campbell recalled.

“I used to watch these militia guys practise. They would line up targets along the pit face with the gravel bank behind. Then the guys would line up and let go. You could see rocks flying off the bank and they’d end up pointing straight up in the air. I think the enemy would have been fairly safe it they had come up against those guys.”

In Gibsons, the men would gather at what is now the Heritage Playhouse, which doubled as a meeting place for a women’s organization. Another hope of McDonald’s is to install a plaque acknowledging the building’s role in the war.

“It’s a matter of recognizing all types of veterans, not just those who went oversees, not just those who were killed in battle, not just those who died in training accidents, but those hundreds of thousands who volunteered,” McDonald said.

Matthew Lovegrove, curator and manager at the Sunshine Coast Museum and Archives, agrees and is hoping McDonald’s search uncovers more artifacts for the archives that could be used for a public display. Aside from a handful of photos, the archives are bereft of PCMR artifacts. “That’s very much a reason to start reaching out now,” Lovegrove said.

At their home, Lottie Campbell recognized her memories aren’t the same. She has no tangible artifacts or photos of her father as a Ranger. “I don’t know where he kept his gun, I know I never had access to it. I would imagine it was probably in their bedroom closet, I don’t know, I really don’t know,” she said.

Despite the lack of relics, Lottie said her father and family were proud of their contribution to the war effort, and lucky they escaped tragedy. “We raised our children and they have avoided all war, too. How fortunate is that?”

And memories of the Rangers have popped up in public from time to time, too. Former Ranger Parr-Pearson’s Coast News alerted the public about the anniversary of the end of the Rangers. Printed in 1981 under the headline, “Thirty-Five Years Ago,” Coast News reported, “The final meeting of the Pacific Coast Rangers, Pender Harbour Branch, was held on January 4 at Irvines Landing for the purpose of purchasing arms. The unit was organized in 1942.”