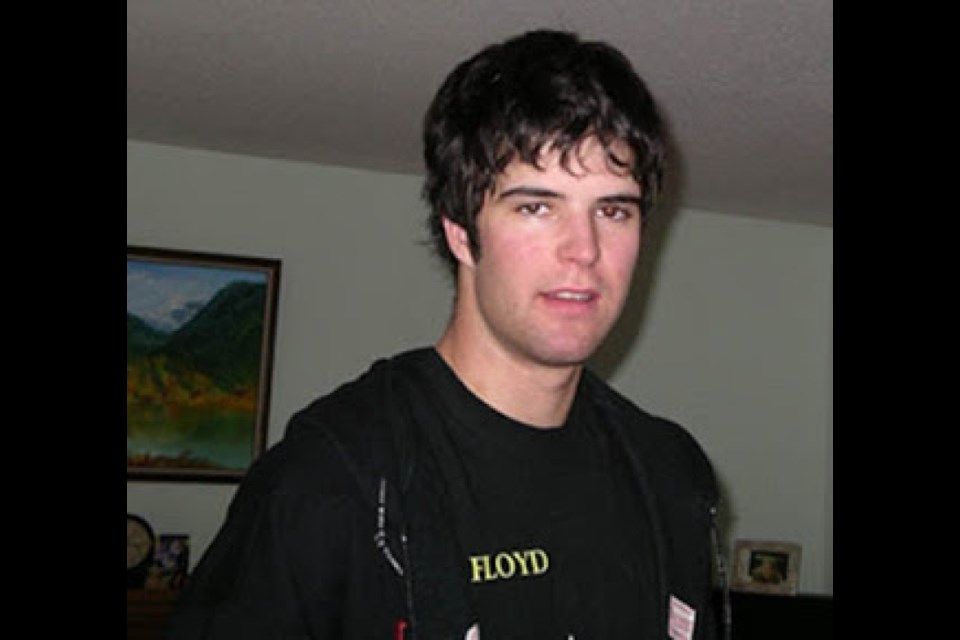

Those carrying the torch for the late Sam Fitzpatrick, who died in a workplace accident in 2009, are calling for a reinstatement of the charges in his death.

Squamish's Fitzpatrick, 24, was killed when a boulder dislodged and rolled down onto him at a Kiewit hydroelectric project in Toba Inlet.

On Oct. 28, Fitzpatrick family friend Mike Pearson and representatives from the BC Federation of Labour (BCFED), the United Steelworkers (USW), and Powell River-Sunshine Coast MLA Nicholas met with the Attorney General, David Eby and Minister of Labour Harry Bains in Victoria, pleading their case for what they see as justice denied for Fitzpatrick and calling for reform of a system they say wronged him.

In August, the British Columbia Prosecution Service (BCPS) stayed the charges against those accused of being complicit in Fitzpatrick's death at the Toba Montrose run-of-river project.

The case against Peter Kiewit Sons ULC (Kiewit), Timothy Rule and Gerald Karjala was set to go to trial on Sept. 7.

"The available evidence no longer satisfies the charge assessment standard for the continued prosecution of the charged corporation and individuals for any criminal offence. As a consequence, a stay of proceedings was directed in the case," the prosecution service said at the time.

The BC Prosecution Service operates independently within the justice system, under the Ministry of Attorney General. Crown Counsel are prosecutors who work for the BC Prosecution Service.

When the Crown Counsel's decision was announced, Pearson, who has been a tireless advocate for Fitzpatrick and his family for a decade, called the decision "devastating."

About the recent meeting, Pearson said, "emotions were palpable in the room. All the people giving their comments to the ministers had to pause at some point to hold back tears or to tame down their thoughts."

"The main theme was, if you are not going to prosecute an egregious case like the Sam Fitzpatrick workplace death, then when and which one?"

Pearson said they discussed the case and why advocates thought it should have and could have proceeded to trial.

"Going forward, we want the Kiewit corporation to be held accountable for what happened to Sam Fitzpatrick on their project site in 2009. The circumstances of Sam's [death] were fundamentally wrong no matter how you look at it," Pearson told The Chief.

"If deterrents against workplace crimes are meant to be effective, there has to be a demonstrated will to use the tools of punishment available to the legal system.

We want our government and legal system to take serious action and support our fight for justice in the case of Sam Fitzpatrick's unnecessary death."

Pearson noted Kiewit is currently working on flood repair work in B.C., something he acknowledged the company is quite good at, but, he said, the lack of closure — in his view a criminal conviction — in Fitzpatrick's death is a blight that should concern all in the province.

When they left the October meeting, the advocates asked for three things:

Firstly, they called for the charges in Sam Fitzpatrick’s death be reinstated.

Secondly, as broader reforms, the advocates asked that two of the recommendations in lawyer Lisa Helps’ report into the Babine Forest Products in Burns Lake explosions, which killed two workers, be implemented in B.C.

"Training of Crown Counsel to investigate workplace deaths and serious injuries; a fund to be set up to train Crown Counsel, which I think is sadly missing," said Stephen Hunt, who represented USW at the meeting.

Thirdly, the advocates asked for workplace-accident-specific training for police officers.

“So, if they are called to a workplace fatality or serious injury, they don't automatically defer to WorkSafeBC, but actually seize the scene and first rule out any criminality,” Hunt said.

This would be akin to a car crash investigation, added Hunt, rather than seeing it more as a WorkSafeBC issue.

"It is not the police's fault. There should be proper training," Hunt said.

Is it even possible to reinstate the charges?

Dan McLaughlin of the BC Prosecution Service reiterated to The Chief that the BC Prosecution Service conducted a thorough review of the Fitzpatrick case and determined that the available evidence no longer satisfied the charge approval standard for a prosecution of any criminal offence. “Accordingly, the BCPS entered a stay of proceedings. That decision was based upon the information and evidence available after extensive investigations which took place over several years,” McLaughlin said, in a written statement.

“The decision could be revisited if the investigative agencies were to submit a further report with new or additional evidence. In that case, the BCPS would conduct a charge assessment. If, based on that new information, the BCPS concluded the charge assessment standard was met a prosecution could proceed.”

McLaughlin noted charging decisions are made in accordance with the Prosecution Service’s charge assessment policy, which requires both a substantial likelihood of conviction and that a prosecution is required in the public interest.

“Crown Counsel make their charge assessment and other prosecutorial decisions impartially, independent of any outside influence, including political influence.”

Attorney General response

The Squamish Chief asked the Attorney General and Ministry responsible for Housing, David Eby, if, after the meeting with advocates, there was anything that his office could do that would help trigger another review of Fitzpatrick's case or if this is the end of the line.

The Chief also asked if, in the wake of this case, there will be consideration of changes to legislation.

A ministry spokesperson noted WorkSafeBC is mandated by legislation to investigate serious workplace incidents, including those that result in the death or serious injury of a worker.

In 2013, the province also reviewed existing provincial and criminal legislation, policies and practices that deal with incidents of workplace fatalities. These were found to be comprehensive, the spokesperson said.

"Providing training for police and workplace safety investigators and having experienced Crown Counsel assigned to these complex cases are also key components in dealing with them effectively."

Westray

Fitzpatrick was not a member of the United Steelworkers (USW), but the union early on took up the mantle to advocate for the Westray law to be enforced in his case.

"It seemed to us at the time and continues today, to ring the bell on a Westray or a Criminal Code trial,” Hunt said.

The criminal charges originally laid in the Fitzpatrick case came May 31, 2019, and were the enforcement of the Westray law.

The "Westray Bill," which became law on March 31, 2004, established a legal duty for bosses and supervisors " to take reasonable steps to ensure the safety of workers and the public."

Most importantly, it created new sections in the Criminal Code of Canada so that corporations and their representatives can be charged criminally if their actions lead to the death of workers.

"We are all victims, in some sense, of Sam Fitzpatrick's death, and we made it known this was handled, we thought, inappropriately in all respects,” Hunt said, adding he doesn't think the Westray Law is one that Crown Counsels want to test in B.C.

"But by doing that, they abdicate their responsibility to the Criminal Code of Canada, I think. That is our argument," Hunt said. "This should be used as a deterrent. It is not a weapon; it is a deterrent. We have said all along...we don't want a whole bunch of CEOs in jail, but one or two would be good."

Employment and labour lawyer Andrea Raso, with Clark Wilson, said one thing to remember in the Sam Fitzpatrick case is that criminal charges were being pursued, and they require a very high standard of proof.

"What came out of Westray was that there should be, over and above occupational health and safety laws, there should be the ability to charge an employer, an organization and any key people involved, with a criminal offence — if it met the standard for criminal conduct," she said.

Because somebody might be imprisoned — lose their freedom — in a criminal case, there is so much more caution that goes into bringing those cases to court and making the decisions regarding them, she added.

"That doesn't mean that there wasn't remedy beforehand, or since the Westray bill came into effect.

Westray is federal legislation. Each province also has its own Occupational Health and Safety (OH&S) laws.

There's always been the OH&S regulations, which are the regulations to the Workers Compensation Act that require employers to take reasonable precautions to protect the health and safety of workers, Rasso said.

For example, she said, a lot of the COVID-19 safety protocols we are now familiar with in workplaces have, over time, risen out of health and safety laws and the protocols required to keep employees safe.

"Those [laws] still exist, they always have existed, and they are always used," she said. "The difference is the penalties under the OH&S. It does not involve the finding of criminal wrongdoing, and therefore there's no prison time."

Typically, instead, OH&S involves administrative penalties or fines.

In Fitzpatrick's case, WorkSafeBC fined Kiewit $250,000 in March of 2011, but that was later reduced to $100,000 by the Workers Compensation Appeal Tribunal.

"Sometimes they can be significant," Rasso said, noting penalties are sometimes in the $600,000 range.

"So, I think employees should have that sense of security that there is that legislation that employers have to abide by. Whether or not it meets the threshold for a criminal offence is a whole other story," she said.

The standard for proof to prove a breach of a statute or a regulation is usually based on the balance of probabilities. In a criminal case, it is proof beyond a reasonable doubt.

"It is that much harder to get a conviction because the standard of proof is a lot higher," she said, adding it is often hard to prove intent with a criminal case.

"That is where situations like the Sam case come in."

Kiewit response

Asked about the advocates' call to reinstate changes, spokesperson for Kiewit, Bob Kula said what happened to Fitzpatrick was a tragic accident, but not the company’s fault.

“We understand the grief that continues to be felt by friends and family of Sam Fitzpatrick and their advocacy efforts to improve worker safety in British Columbia. Nothing has been or will ever be more important at Kiewit than the safety of everyone on our projects and to help ensure our worksites are as safe as they possibly can be. It was always our company’s firmly held belief, and that of our experts, that the rockfall that tragically took Sam’s life was an accident not caused by those working on the site,” he said in a written statement to The Chief.

“In August, based on the best advice of their own experts, the British Columbia Prosecution Service came to the conclusion that anything to the contrary did not pass the burden necessary to go to trial.

“None of that takes away from the tragedy of what happened to Sam, but an attempt to assign criminal blame where criminal blame does not exist doesn’t do anything to protect worker safety. We will continue to work hard to provide safe workplaces wherever we operate and ensure we’re doing our part to promote and drive safe work practices in construction.”