The Sunshine Coast Regional District (SCRD) is focusing on rural lands in Halfmoon Bay as potential locations of a new 10-hectare (25-acre) landfill site.

The new site would replace the Sechelt Landfill, which is the only receptacle for all Sunshine Coast solid waste, and which has been estimated to have five years remaining capacity, until early 2026.

At a Jan. 20 special meeting of the SCRD infrastructure committee, the SCRD board of directors received a staff report on landfill issues and viewed a presentation by consulting engineer Wilbert Yang, of Tetra Tech Canada Inc.

Directors were given four options, ranked according to several criteria, among them: environmental risks, capital and operating costs, job retention, and greenhouse gas emissions.

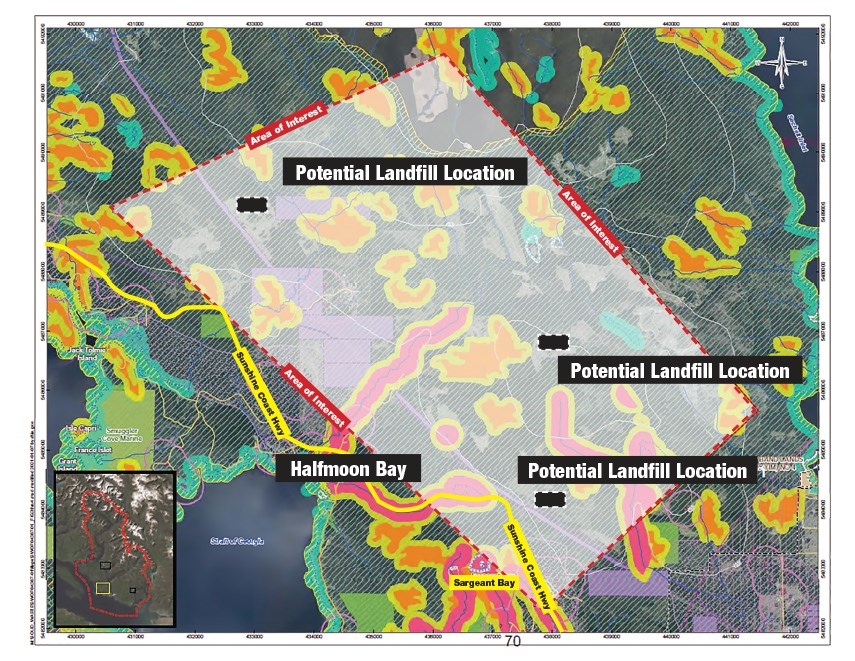

Ranked as Option No. 1 was a new landfill site located on the Coast. Rural sites near Egmont and Langdale were considered, but three potential Halfmoon Bay locations, all east of the Sunshine Coast Highway, were determined to be the best choices.

Option No. 2 was to export the waste off-Coast. That would require the construction of a transfer station from which the waste would be barged for disposal at a third-party site, potentially located in Oregon, Washington, and the B.C. Interior. A risk with this option was a lack of reliable availability, as a third-party landfill site could cancel a contract or close down.

Option No. 3 was development of a waste-to-energy plant. While it had the highest job-creation potential, it was the most expensive option and would require extensive government pre-approvals. It also was most limited in the types of waste it could process and would have to shut down for up to eight weeks a year for maintenance.

Option No. 4 was expansion of the Sechelt Landfill site, which was potentially less expensive and had fewest regulatory hurdles. But, as no adjacent land is available to expand to, and it would require “vertical expansion,” which means digging deeper into the footprint of the current site, the option was determined to be at best a short-term solution.

Yang told directors that the regulatory process for a new local landfill could take up to two years, with a further three years needed to prepare a site. As the Sechelt Landfill might be operational for only five more years, and as a new landfill runs the risk of not being approved after a two-year process, directors had to also pursue a second track and approved the staff recommendation to proceed with further assessments of Option No. 2, to export waste off-Coast.

Capital costs

Preliminary estimates of capital costs for a new landfill – over a 30-year lifespan, from 2026 to 2056 – range up to $13.5 million, or as much as $24.78 per tonne of waste, Yang’s presentation showed. Annual operating costs were estimated at up to $3.5 million, or as much as $195 per tonne.

Current estimates of capital costs associated with exporting waste top out at $5.5 million, or as much as $10.10 per tonne, with annual operations as much as $6.2 million, or $340 per tonne.

The cost of a waste-to-energy facility varies greatly, depending on the type of technology used. The most feasible would be hybrid gasification, with capital costs of $29 million and annual operating costs about $3.3 million. There’s an added cost of disposal of the burned-waste residue produced by the facility. Total per tonne costs could be more than twice as high as that of a new landfill.

Area D (Roberts Creek) director Andreas Tize asked Yang if greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions would be a concern with a new landfill. Yang replied that modern landfill standards make GHG capture a priority. “That facility would be designed to the highest standard necessary in terms of collecting greenhouse gases,” he said.

Sechelt director Darnelda Siegers raised the prospect of future SCRD boards having to repeat this process in another 30 years. She asked staff if they could find 20 hectares rather than just 10.

“It’s certainly advantageous to do more if you have that opportunity,” said Yang.

“Some communities, for instance Kelowna, have 70 to 100 years of capacity. The Capital Regional District (Victoria) is trying to develop their program so that they have at least 100 years of capacity.”

Remko Rosenboom, general manager of infrastructure services, said staff would investigate the possibility of more land acquisition and include that in a report when they return to the board this summer with results of further studies.