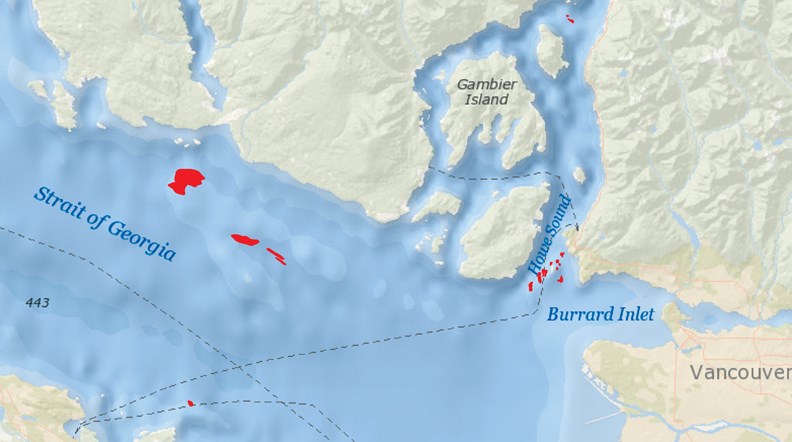

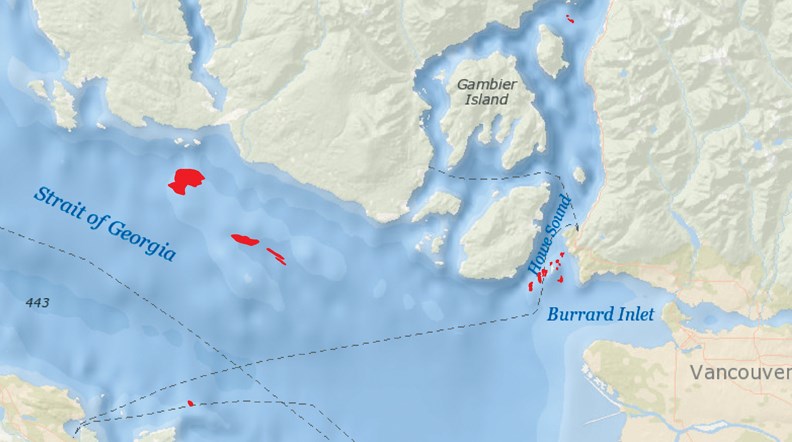

In a victory for conservation groups, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) officially closed B.C.’s rare glass sponge reefs to all types of fishing – including reefs mapped in Howe Sound and off the coast of Sechelt.

As of June 5, a 150-metre buffer zone has been set around each reef. Although there isn’t a physical sign in the water, the GPS locations of the reefs are available on the DFO website (www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca) and anyone caught fishing illegally around the reefs would be subject to fines or tickets.

Cindy Harlow of the Sunshine Coast Conservation Association is heralding this as a major win.

“On the Sunshine Coast, local citizens have been asking for many years for protection of our glass sponge reefs, so we are looking forward to our community taking a stewardship role and working with DFO staff and fisheries to ensure the long-term safety of these amazing ecosystems,” Harlow said.

The first of the glass reefs was discovered on B.C.’s northern coast in 2001 by sea floor mapping done by the federal government under Natural Resources Canada.

The B.C. coast is the only location in the world where this type of reef grows, which is why conservation groups have been fighting so hard to establish buffer zones around them.

“It’s really important, because if people want to continue to have fish and prawns, these reefs provide really important habitats for those and other species,” said Sabine Jessen, national oceans program director at the Canadian Parks and Wildlife Society (CPAWS). “They exist nowhere else in the world, so we should all be trying to do our best to protect them.”

Jeff Marliave, vice president of marine science at Vancouver Aquarium, said research shows the reefs to be “tremendously important ecosystems. They filter large amounts of bacteria from sea water and they provide habitat for a host of other species including endangered rockfish and the much-loved B.C. spot prawns.”

Forty million years ago, glass reefs were more pervasive, specifically in the Tethys Sea – a prehistoric body of water that existed before the continents drifted to where they are now.

“We don’t really know why they’re only here,” Jessen said. “Except that somehow the conditions must be just perfect for them. They rely on a lot of dissolved silica. Silica basically is glass. It’s dissolved in the ocean water and likely comes from the adjoining mountains. That dissolved silica is critical to their growth.”

The glass reefs found north of the Georgia Strait are roughly the size of an eight-storey building. The sediment at the bottom of these reefs has been dated to about 9,000 years ago, around the end of the last ice age.

“In the Strait of Georgia they’re generally smaller and only comprised of two of the three species that are reef forming,” Jessen said. “The reason they are able to form reefs is because the skeleton of the animal stays intact when the animal dies. So the new sponges grow on top of the dead sponges.”

CPAWS has been trying to get the closures put in place, but it’s taken about six years to have the buffer zones implemented.

More reefs in Howe Sound have been discovered since 2001. These do not have buffer zones in place, but CPAWS is trying to get them established.

“Our hope is that we can get those protected a little faster than in six years,” Jessen said.