PHOENIX — A border wall. Smugglers. Small children being dropped into America in the darkness.

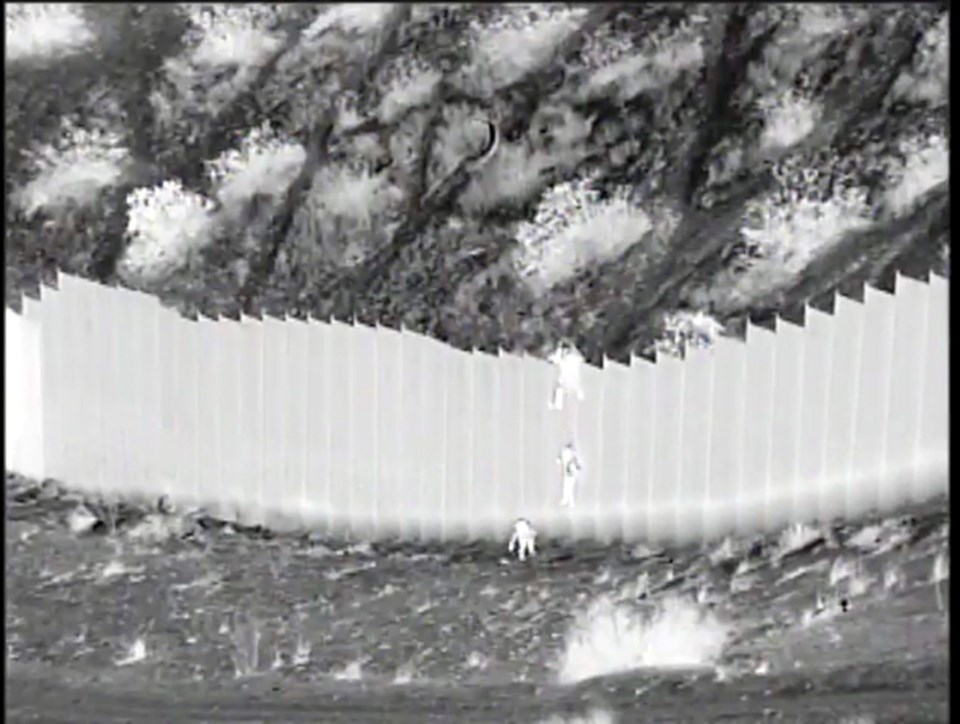

A grainy video released Wednesday by authorities — its figures visible only in ghostly white outline, its stark storyline dramatic and obvious — captures, in mere seconds, the dangers for migrant children at the southern U.S. border.

A man straddling a 14-foot (4.3-meter) barrier near Santa Teresa, New Mexico, lowers a toddler while holding onto one arm. With the child dangling, he lets go. She lands on her feet, then falls forward face first into the dirt. The smuggler does the same thing with a slightly larger child, who falls on her feet and then her bottom. Then the smuggler and another man run off into the desert, deeper into Mexico.

The simple scene caught by a remote camera is an extreme case. But it embodies so much of the saga playing out on the border amid a spike in migrant arrivals, particularly children.

There is implied desperation — a family willing to subject their children to such risks in hopes of changing their future. There is the callousness of the smugglers handling kids like rag dolls.

And there is that barrier over which so many have fought — a symbol of American strength for some, a decidedly un-American thing altogether for others. A fence that, despite its height, is relatively easily overcome.

For immigrant advocates, scenes like this underscore why immigration laws need to be overhauled with a focus on unifying families and making legal immigration easier. For many opponents of such reform, scenes like this are confirmation that the nation's rule of law isn't being respected, that a reform of immigration policies could never even be contemplated while such things are happening. And Americans of all political stripes may debate what circumstances, if any, justify parents taking such actions.

While such debates happen, thousands of migrants from Mexico, Central America, and countries further south are arriving every day to the Mexico-U.S. border. Many are fleeing violence or other hardships in their home countries. Others are simply looking for better economic opportunities. They arrive by boat or wade through the Rio Grande River in Texas, or come on land into California, Arizona and New Mexico.

Many are children

Unlike their parents in many situations, all unaccompanied minors are allowed to stay in the U.S. That dynamic has prompted many parents to either send kids on the journey to America alone, or get to the border and let them go the rest of the way. Most end up at least temporarily in shelters that are currently way beyond capacity.

Border authorities said the children caught on video were sisters, ages 3 and 5, and from Ecuador. They were found alert, taken to a hospital and cleared of any physical injuries. As of Thursday, they remained at a Border Patrol temporary holding facility pending placement by the U.S. Health and Human Services Department.

The girls’ mother is in the United States and authorities are in contact with her, Roger Maier, a spokesman for U.S. Customs and Border Protection, told The Associated Press on Thursday. Maier couldn’t provide more details.

Many children arriving alone have relatives in the United States. If they are too young to remember names or phone numbers, as these girls likely were, they may come with contact information written down on paper or directly on their bodies. After being processed by the Border Patrol, they are transferred to Health and Human Services. Eventually they will be released to a sponsor, usually a parent or close relative.

The hope of those who send the children is that they will eventually be reunited with family in the U.S. But the risks to get to that point are enormous.

They can come from

“People considering using the services of smugglers need to know that smugglers don’t have the kids’ best interest at heart. It’s entirely too dangerous,” said Maier, who added this about the girls being dropped: “Had it not been an area that was monitored, these children would have been fending for themselves.”

____

Peter Prengaman is the Associated Press' news director for the western United States. Follow him on Twitter at http://twitter.com/peterprengaman

Peter Prengaman, The Associated Press