Mealtimes by the Caspian Sea were always displays of abundance. Omid Roustaei's extended family would gather every summer, swimming at the beach in the morning and returning to mounds of food at the family villa.

Pomegranate, bitter orange, dried lime, walnut and olive appeared on repeat. The earthy scents of cumin and coriander blended with sweeter cinnamon and cardamom — maybe even pulverized rose petals.

Plus, there were herbs. Handfuls of parsley, cilantro and dill tossed into stewing pots and served by the bunch for munching at the table.

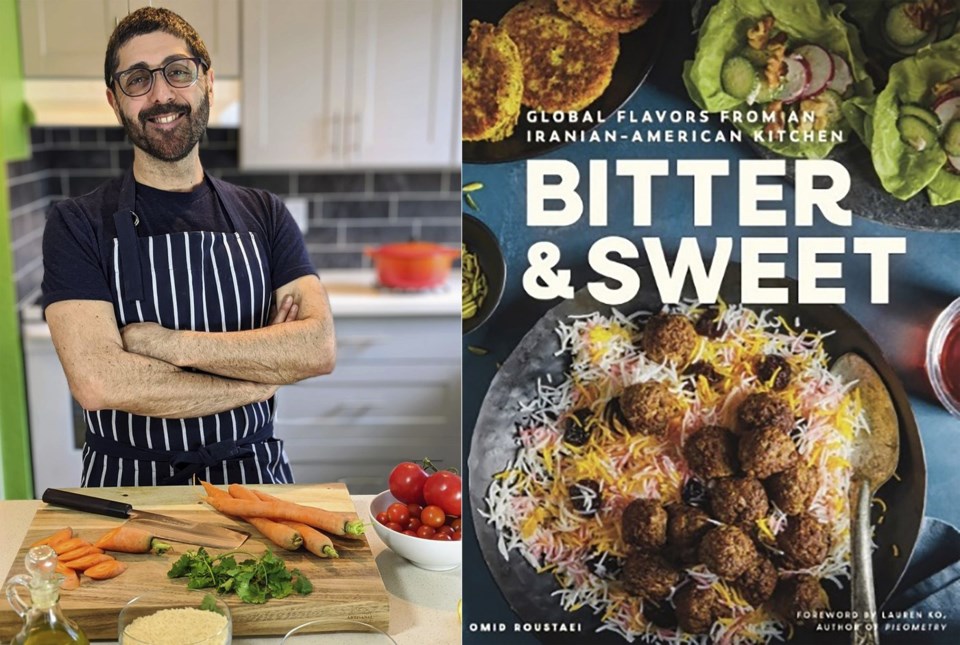

“To us in Persian food, herbs are not treated as little, cute things you put on the side of the plate, but rather herbs to us are vegetables," said Roustaei, author of the new cookbook “Bitter and Sweet: Global Flavors from an Iranian-American Kitchen.” “When we cook a dish, we use mounds of herbs.”

The tranquility of a childhood mixing cosmopolitan Tehran with summers in the north would be shattered when he was about 10 years old. The Iranian Revolution was brewing, and several years later he left the country, first going to the Netherlands and then Arizona.

It took decades for Roustaei to return to his Iranian roots and explore the cuisine of his youth. Eventually, he made his way to Seattle, began giving cooking classes, and started a blog called The Caspian Chef.

Besides making tasty meals, Roustaei hopes that making Iran's culinary traditions more visible serves as a type of diplomacy. He sheds light on universal traditions, like caring for your family and bringing people together.

“Through the food, which always feels like this safe gateway, it allows people to get to know Iran and who Iranians truly are,” said Roustaei, who is also a psychotherapist.

He attempts to demystify what is a fairly complex cuisine. What Iranians consider “plain rice,” for instance, is actually more of an art form. The rice is scented by saffron and maybe mixed with yogurt, which produces light and fluffy grains with a crispy layer of golden tahdig, meaning “bottom of the pot.”

The book is filled with dishes that would have been familiar on that long-ago family table, but many include personal twists that reflect a modern lifestyle.

One, khoresh fesenjun, reminds Roustaei of his mother. Bone-in chicken is braised in a dark sauce made from sauteed onions and ground walnuts. Reflecting Iranians’ penchant for sour flavors, the sauce is brightened by sweet-tart pomegranate paste, which is made by patiently simmering the vibrant juice until most of the liquid evaporates.

Since she didn’t have a food processor, his mother crushed one walnut at a time on a wooden tray, mashing each piece with a river rock. Making it took hours.

For the average American home cook, a food processor or blender gets close enough, and pomegranate molasses is easier to find than the paste. It will still be delicious, evoking the pleasures of the Caspian Sea.

“I find it to be really easy to prepare, accessible and yet profoundly unique in its taste,” he said.

The recipe:

Chicken in Pomegranate and Walnut Sauce

From “Bitter and Sweet: Global Flavors from an Iranian-American Kitchen,” by Omid Roustaei

Ingredients:

2 cups walnuts

2 tablespoons neutral oil

4 chicken thighs (about 1 1/2 pounds), bone in and skin on

1 onion, diced

1/2 cup pomegranate molasses

1/2 cup water

1/2 teaspoon sea salt

¼ teaspoon ground black pepper

2–4 tablespoons sugar (optional)

1/2 teaspoon saffron threads, ground and bloomed in 1 tablespoon hot water

Directions:

In a food processor, chop the walnuts and process until finely ground. Set aside.

In a Dutch oven over medium-high, heat the oil and cook the chicken, skin side down until golden, about 5 minutes on each side. Place the chicken on a plate, and set aside. Lower to medium, cook the onion until aromatic and lightly golden, about 10 minutes.

Add the walnuts to the onion. Reduce to medium-low and stir continuously for 2–3 minutes. The walnuts should appear slightly dense and sticky. Add the pomegranate molasses, water, salt, and pepper and stir to combine.

Return the chicken to the pot and immerse in the sauce. Partially cover the pot with the lid and raise the heat to simmer gently. When it bubbles, reduce to low and cover. Stir occasionally and scrape the bottom with a flat-edge spatula to inhibit crusting. After 40 minutes, taste the sauce and add more pomegranate molasses or sugar if needed. You’re aiming for a robust pomegranate flavor with a balanced sweet and tart profile.

Simmer until the sauce becomes deep maroon and the chicken falls off the bone, up to another hour. Stir in the bloomed saffron.

Turn off the heat and let stand covered for 10 minutes. The natural oil from the walnuts and chicken will rise to the top. That’s a sign of a khoresh that is jā-oftādeh, a Persian culinary term for a well-prepared stew.

Serve with steamed basmati rice.

EDITOR’S NOTE: Albert Stumm lives in Barcelona and writes about food, travel and wellness. Find his work at https://www.albertstumm.com

___

For more AP food stories, go to https://apnews.com/hub/food-and-drink.

Albert Stumm, The Associated Press