The owner of Kitsilano’s Corduroy restaurant has recently made waves for her selfish decision to continue to have indoor dining, despite current health orders in B.C. When health authorities attempted to enforce the orders, she persisted in running in-person dining at the restaurant.

When health authorities shut the restaurant down, she continued to serve customers in the restaurant.

Things came to a head this weekend, when the owner and her patrons were captured on film harassing health officials, chanting at them to get out of the restaurant. The City of Vancouver has since suspended the restaurant’s business license.

In the midst of all of this, owner Rebecca Matthews has posted Instagram posts (now private) justifying her decision to remain open, including a post in which she claimed that “we cannot continue to protect certain lives by destroying others.” While such a view is troublesome in and of itself, what is more troublesome appears to be the root of her decision to defy orders.

What is the "common law" or "freeman" argument?

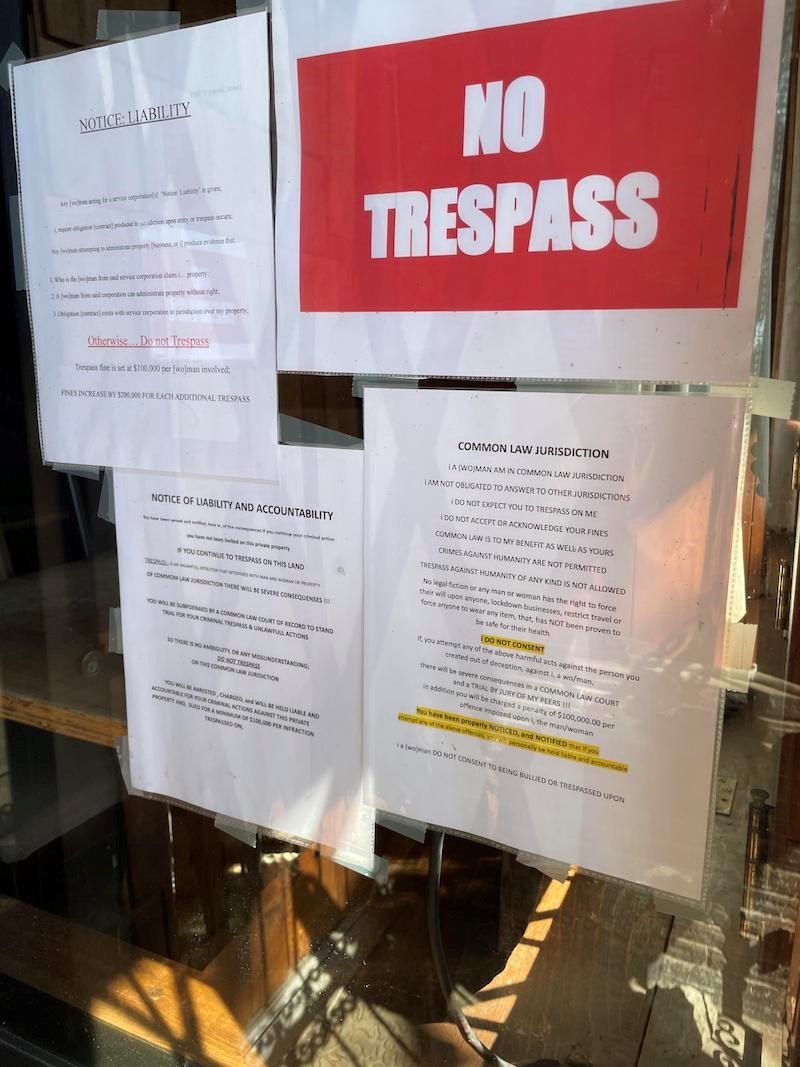

A photograph recently posted to Reddit shows the front door of the restaurant, plastered with signs that indicate the restaurant is “common law jurisdiction” and that fines will be imposed, commencing at $100,000 against any health officials who attempt to enforce the closure orders.

But what exactly does this mean?

The official legal answer is “nothing.” What the signs on Corduroy’s doors refer to is a type of pseudo-legal argument that has been raised in various contexts, by individuals attempting to avoid various legal sanctions by government.

You may have heard of this argument in its other forms - “freeman of the land” or the “natural person” argument. The crux of the argument is that individuals are governed by free will only, and unless they enter into a binding contract with the state — which they have not done — then they cannot be governed by the state’s authority over them. The argument has been raised to fight taxes or traffic tickets.

The courts have unilaterally rejected the plausibility of these arguments. The most-frequently cited case for this is Meads v. Meads, an Alberta divorce case, in which Mr. Meads attempted to advance what the court characterized as an “Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Argument." And as the courts have termed these arguments such, the names used by the — is it fair to say wing nuts? — advancing them have shifted.

Proponents of the arguments change the names but not the substance of the way in which the arguments are concocted. And the manner in which this has been done is clever.

"You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.”

If you were to read about these arguments, without a legal education, you might be persuaded to believe that there is some truth to them. For example, the arguments will often refer to very old statutes like the British North America Act or principles of Admiralty Law as the source of the legal conclusion. The arguments themselves draw from real language used by lawyers and in court all the time.

The notices posted on the doors of Corduroy refer to the restaurant being in common law jurisdiction. Without reading anything that follows, that is technically true. British Columbia is a common law jurisdiction. But, to quote Inigo Montoya, “You keep using that word. I do not think it means what you think it means.” Common law jurisdiction does not refer to the right of a person to make their own rules and live by whatever rules they want. Rather, it refers to a legal system that is governed by laws as interpreted through the courts. Judges create precedent, which creates and shapes the law.

But the power in a common law jurisdiction lies with judges. And judges in B.C. have consistently rejected the notion that the health orders designed to protect against the COVID-19 pandemic go too far.

Even in a common law jurisdiction, government still has power. Statutes are written and interpreted by the courts, who determine what the government intended when they wrote the law. But the government still retains power to write rules and, to some extent, bind the hands of judges with those rules.

Nothing in any legal sense of the term “common law jurisdiction” implies that Corduroy can exempt itself from complying with public health orders, or fine health officials or trespass.

Are Vancouver Coastal Health inspectors 'trespassing' while enforcing an order? No.

The signs prohibiting trespass, which are recommended notices in the handbook of pseudo-legal babble, take their roots from British Columbia’s Trespass Act, which itself has a section on prohibiting trespass. The Act provides remedies to victims of trespass who post such notices on their properties.

So if you were to look it up, you might see that it is connected to something that seems real. That’s the trick with these arguments. They are just close enough to the real law that it is easy to be fooled.

Even trespass itself is a loaded term. Trespass, in a common law jurisdiction, refers to a tort. That is a civil wrongful act of entering onto the property of another person, without the right to do so. Health officials are granted permission to enter restaurant premises and, in fact, any premise to enforce public health orders. And, of course, the Trespass Act states that it does not apply to people who enter a premises with lawful authority.

Oh, and the $100,000 fines for trespass on the restaurant property? Well, those fines are not something that can be imposed by an individual. In a civil suit for trespass, the court would determine the amount of the financial award, which would be limited to the damages suffered by the trespass. That would be exactly $0 in a case like this given that no trespass has or can occur.

The 'rights' you give up when owning a business

But even entertaining for a moment (I can’t believe I’m doing this) the notion that Ms. Matthews needed to enter into a contract with the state in order to give up her rights… she did.

By applying for a business license, she entered into a contract with the City of Vancouver. By applying to be a food-serving establishment, she entered into a contract with the Health Authority that included the power to inspect and enforce health orders. By applying for a GST and PST number, she entered into a contract with the provincial and federal governments to collect and pay taxes. Ditto for the liquor license. And the lease, assuming she does not own the property, likely contains standard terms about illegal activity.

If her position is that a contract cannot be unilaterally imposed upon her by the state, then she cannot unilaterally undo all the contracts she entered into when starting the restaurant. Even assuming her arguments as posted on the door had any legal merit, which they do not, they are not applicable in her case.

Kyla Lee is a Vancouver-based criminal lawyer