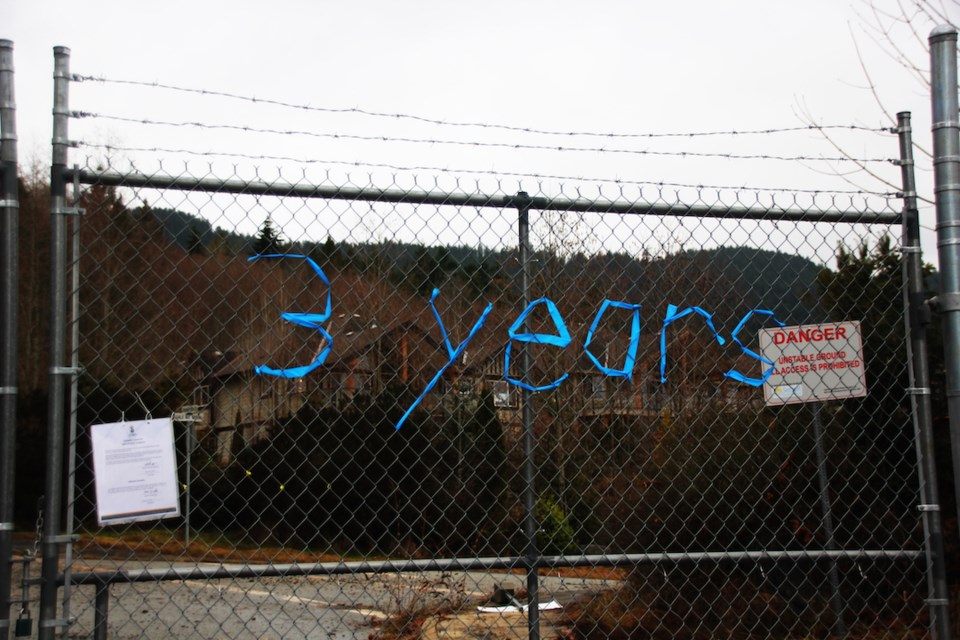

I have written more than a dozen stories related to the Seawatch subdivision in the last year. Since Sechelt’s state of local emergency (SOLE) enacted in 2019 ended in February, the public remains excluded from the neighbourhood of 21 properties – 14 homes – as Sechelt says that it remains unsafe.

The saga of Seawatch spans decades and with another recent BC Supreme Court filing by some homeowners, there are few signs of a resolution any time soon.

This piece begins with full disclosure. I was an employee of the District of Sechelt from 1997 to 2018. That period covered the approval and build-out of the subdivision as well as the development of sinkholes on roads and near residences in 2013 and 2015. In my last four years with the District, disagreements between property owners, the municipality and others developed, which led to legal actions, investigations and multiple meetings with geotechnical and legal advisors. By Christmas 2018, when an additional sinkhole daylighted, I had retired from the District (and returned, part time, to journalism).

The Seawatch story is one that I’m close to. I have heard the heart wrenching accounts of those forced to leave their homes. I have also read the court paperwork that supports the municipality’s position that the owners bought their properties encumbered by a covenant that provided them with details on the site’s geotechnical conditions.

Words like “buyer beware” come to mind. In my own real estate investments, I have dealt with covenants. They can seem innocuous, a notice that something may or may not happen. In the case of Seawatch, that “something” happened. And when it did, the investments and dreams of people who purchased properties became as unstable as the ground their homes were built on.

With the benefit of hindsight, the troubling part is that the development was allowed to proceed. Permits were issued to build infrastructure and homes, and to allow those homes to be purchased, mortgaged, and moved into. Numerous sign-offs by different authorities and highly trained individuals had to occur before the new homeowners hosted “housewarming” parties.

Yet all rolled along as if nothing was wrong until June 2013 when a portion of Seawatch Lane disappeared moments after a family vehicle passed over it.

I was at the District office reception desk the day that distraught driver came in to report what had happened. From the description provided, it seemed serious. Little did I know how serious it would get. I do recall my fingers were shaking as I dialed the phone to summon someone from the engineering department to the front counter to deal with the situation.

In my time with the District, there had been difficult situations in but nothing that would rival Seawatch. Fortunately, to date, the losses have not included damages to human life or safety.

But, Seawatch has exposed things that are wrong with our society. The decisions to not share information, be that by oversight or design, speaks to the lack of compassion humans can display to one another.

In less than five years, Sechelt went from saying, it is OK to consider building to closing the area over life safety concerns. Its present position is covered in a website statement: “the Seawatch subdivision is unsafe for human occupation due to the danger of sinkholes.”

And the negative impacts of having an abandoned and not adequately monitored group of high-end homes just past their doorsteps is creating issues for neighbours of Seawatch.

The penchant to avoid taking responsibility for what one did or did not do that caused harm to someone else seems to be supported by our modern legal system. Even if you know you are wrong, if you drag it through the court system, you may be able to wait the other party out. This appears to be the approach several involved with the fiasco are taking.

Accurately predicting the future or knowing exactly what is happening beneath the surface of the ground is not something humans are good at. To mitigate risk in dealing with the unknown, we lean on the modern construct of “insurance.” But that system has limits and allows professionals, whose opinions a layperson may put their faith in, to avoid liability through “disclaimers.”

I watch Seawatch because it is my job. Because the site is in this paper’s home community and affects people who live here. Because this community needs to examine what went wrong and how to do better next time.

I watch the story as it unfolds through the courts in hopes that right will prevail. What’s right? I don’t know. My hope is that it is a compromise where all parties involved share in the responsibilities, based on the level to which their ill-fated decisions contributed to the calamity. Be it imperfect and expensive, our justice system exists to deal with how we mistreat one another. And it’s important to remember that any reparations that local or provincial governments are ordered to pay will come at a cost to all taxpayers in the jurisdiction involved.

I also watch, unfortunately, because I can’t look away. Like a car crash on the side of the road or a structure fire, I know someone else is having a very bad day. But I watch and self-centredly think “thank goodness it’s not me.”

Full disclosure: I’m a human and I have made questionable decisions, just like the other humans involved in Seawatch.

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)