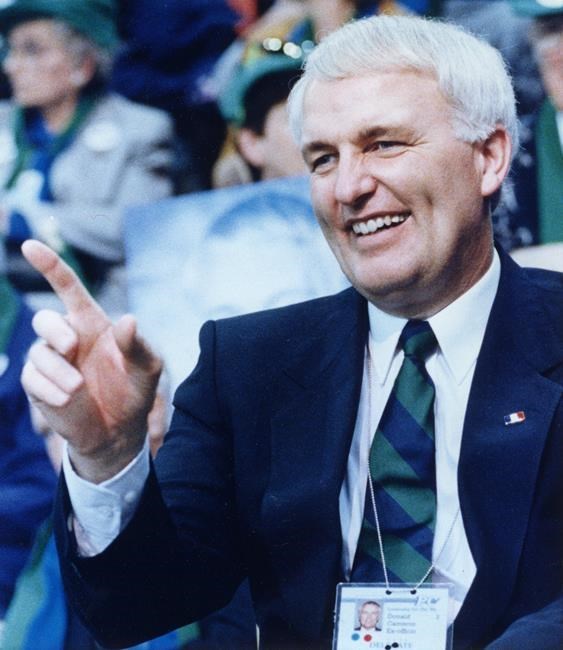

HALIFAX — Raised on a farm in Nova Scotia's Pictou County, Donald Cameron's rural roots were a source of pride for a man who in 1991 would become the province's 22nd premier and an advocate for fairness and social justice.

An avowed deficit-fighter who pledged to rid the province of patronage, Cameron died Monday at the age of 74. A cause of death was not disclosed.

"He was ahead of his time," former prime minister Brian Mulroney said in an interview Monday. "He took decisive action in areas that cemented Nova Scotia's reputation as a social leader among Canadian provinces."

Among other things, Cameron's one-term government introduced pioneering human rights legislation that called for equal rights for gay and lesbian people.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, in a statement of condolence to Cameron's family and friends, colleagues and Nova Scotians, recognized that legislation for "helping make Canada a fairer and more equal country."

“Mr. Cameron will be fondly remembered for his many years of service in his beloved home province, his integrity, as well as his commitment to transparency, equality, and human rights," Trudeau said.

Cameron also helped make it possible for a predominantly Black area east of Halifax to elect the province's first Black member of the legislature in 1993.

"He was a very principled man and a great representative of Pictou County," said Mulroney, who recalled how Cameron helped him on his first successful campaign to win a federal seat in a Nova Scotia byelection in 1983.

Mulroney also said Cameron was a key player in the prime minister's 1992 bid to get Quebec to sign the Constitution through the ill-fated Charlottetown accord: "He provided fair-minded leadership to the premiers and the federal government at the time .... He provided outstanding leadership during that period."

Born in Egerton, N.S., Cameron was raised on a family farm and later graduated with a bachelor of science degree from McGill University in Montreal in 1968. When he returned to Nova Scotia, he converted Sunny Cove Farm into a dairy operation and would proudly describe himself as a shy farm boy from a deeply rural corner of the province.

''I went to school and went home and did my chores. I never took part in sports or anything,'' Cameron, a church-going Presbyterian, said in an interview with The Canadian Press in February 1991.

He married McGill classmate Rosemary Simpson in 1969 and the couple had three children: Natalie, David and Christine. Married for 51 years, Cameron lost his wife to cancer less than four month ago, on Jan. 17. She was 73.

First elected to the Nova Scotia legislature in 1974, Cameron was never defeated in Pictou East. He held a handful of cabinet posts, including the fisheries and industry portfolios. And on Feb. 9, 1991, he won the leadership of the Tory party after three ballots, replacing the scandal-plagued John Buchanan as premier.

Cameron campaigned on a platform that promised to reduce the province's budgetary deficit and to shrink the government's firmly entrenched system of patronage, a pledge that would come to define his career in politics.

George Archibald, a former cabinet minister in Cameron's government, said the two first met in 1964 when they were studying at the Nova Scotia Agriculture College.

Archibald said Cameron's political ethos was based on fairness. When he was elected to the legislature, one of the first things Cameron did was end the practice of hiring and firing all the snowplow drivers and road crews based on their political affiliation.

"They expected to get their termination notice immediately because that's the way it always happened," Archibald said in an interview Monday. "But not with Donald."

Cameron also introduced measures to reduce patronage in the appointment of judges, and he allowed for an exemption to the electoral rules to create a riding where the local Black population had a better chance of electing one of their own to the legislature.

"It was about being fair to everybody," Archibald said. "That was a milestone. Donald did that."

Nova Scotia Premier Iain Rankin issued a statement, praising Cameron's dedication to public service. "He will be remembered for his integrity and commitment to human rights," he said.

Under Cameron's leadership, the Tories tabled a budget that raised the cost of prescription drugs for seniors, froze provincial wages for two years and eliminated 300 public service jobs. As premier, he sold the government's private airplane and he ordered all cabinet ministers to lease economical vehicles.

"I don't know that he ever charged a meal to his government expense account the whole time he was premier," Archibald said.

Cameron's term as premier was also marked by the Westray mining disaster in Pictou County on May 9, 1992.

Early that morning, an explosion in the mine under Plymouth, N.S., killed 26 miners and triggered immediate demands for an investigation. Six days later, Cameron's government appointed Nova Scotia Supreme Court Justice Peter Richard to conduct a public inquiry, which started hearings in 1995.

Evidence presented to the inquiry in 1996 suggested Cameron went to great lengths to win approval for the mine, which held the promise of well-paying jobs for constituents in his and neighbouring ridings. At the time, Cameron said his political fortunes were not a factor, because the mine had been proposed before he was appointed as industry minister in 1988.

Cameron's government was swept from power by the Liberals under John Savage on May 25, 1993. The silver-haired politician retired from politics that night.

In June 1993, Mulroney appointed Cameron to serve as consul general in Boston.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 3, 2021.

Michael MacDonald, The Canadian Press