Content warning: This article contains references to residential school trauma, physical and emotional abuse, intergenerational trauma, domestic violence and substance use.

Parenting is never easy.

It’s a journey filled with joy, challenges, and constant learning.

How can you raise children to feel loved, secure, and proud of themselves while you’re still healing from generational wounds?

For many Indigenous families, this question isn’t just about parenting—it’s about survival, healing, and rediscovery.

Randall W. Lewis, Deanna Lewis, and Anjeanette Dawson have all asked themselves these questions.

Their journeys as parents show their commitment to their children and their efforts to heal, and rebuild connections to culture, family, and identity.

These are stories of resilience expressed through everyday acts of love and hope.

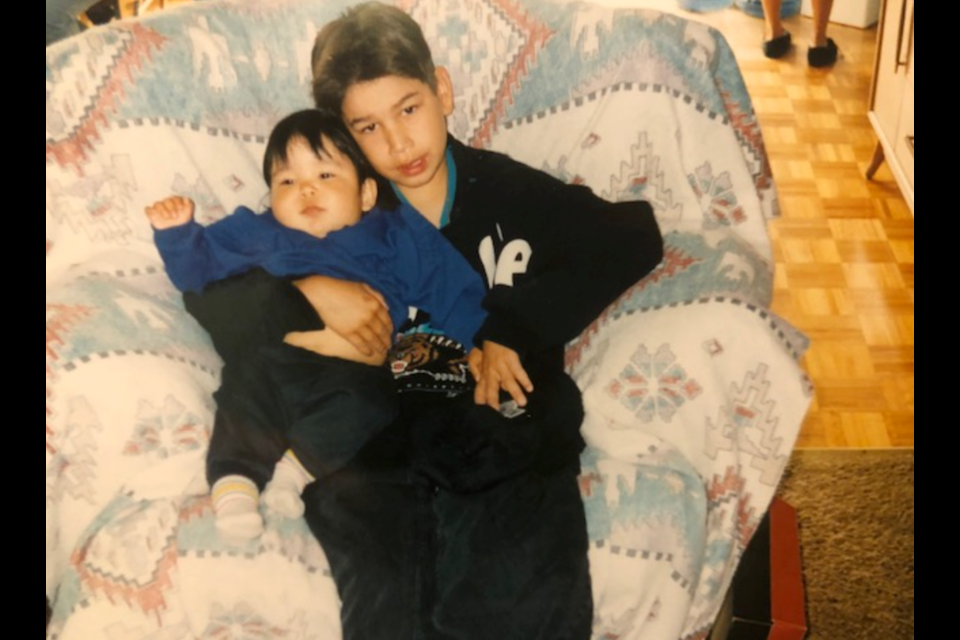

A father’s promise: Ta’hax7wtn’s story

“I told myself my kids would know they are loved every single day,” said Ta’hax7wtn Siyam, who is also known as Randall W. Lewis says, while sitting on a bench near the Welcome Gate sculpture at the Squamish oceanfront.

(The Squamish Chief is using first names with sources who share the same last name.)

Randall is a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw member and a founder of the Squamish River Watershed Society.

His voice carries both pride and reflection.

“Every morning, I hugged my sons, told them I loved them, and they did the same.”

For Randall, this commitment wasn’t just about his sons, Randall Jr. and Dallas, it was about changing the story of his family.

‘They beat the love, the hugs, the kindness out of him’

Randall's parents, Elizabeth Pauline Rush/Lewis of Port Alberni and Allen F. Lewis of Squamish, carried the weight of their own painful histories.

Despite the traumas they endured, they found each other and began a life together far from the residential schools that had shaped so much of their early years.

“They met in Seattle at a Glenn Miller concert,” Randall said. “My father bolted from B.C. to escape the prejudice and colonization of the time. My mother fled Port Alberni for the same reasons. That’s where their story began.”

Elizabeth attended Alberni Residential School, while Allen was taken to St. Paul’s Residential School in North Vancouver.

For Allen, the trauma began when he was just seven years old, when he was punished for speaking his Sḵwx̱wú7mesh language.

“He didn’t speak for three or four years after being taken to residential school,” Randall recalls. “He didn’t even understand why he was being punished until another student told him, ‘Stop speaking your language.’”

The punishments were harsh and unrelenting.

“My dad endured beatings, whippings, and days locked in closets,” Randall says.

“Imagine being a child and going through that. My dad didn’t know how to show love because they beat the love, the hugs, the kindness out of him.”

Randall saw this struggle firsthand as he tried to connect with his father.

“I tried to hug my dad and tell him I loved him, but because of residential school, he didn’t know how to reciprocate or show love,” Randall shared.

Elizabeth’s experience at Alberni Residential School was equally harrowing.

As a young girl, she witnessed and heard about atrocities at the school, including sexual abuse and worse.

‘What happened to Rand’s arm?’

The trauma Elizabeth carried shaped her parenting in ways she later came to regret.

The “discipline” she imposed on her children mirrored the harsh methods she had learned in the residential school system.

Randall recalls one traumatic incident from his childhood.

“My sister Linda and I had started a fire while trying to burn tall grass around the house to help with chores. My mother got very upset and disciplined me. She ran my arm up and down the flame of a propane stove, and I got severe burns.”

When his father came home, he noticed Randall’s injuries immediately.

“He asked, ‘What happened to Rand’s arm?’ My mom said, ‘He was playing with fire, so I burned him.’ My dad immediately took me to the hospital, where they treated me for third-degree burns.”

Years later, when Randall was in his 30s, his mother apologized for what she had done.

“She saw the scars on my arm and said, ‘I’m sorry, son. I did that to you.’ I told her, ‘Mom, it wasn’t your fault. That was what you were taught in residential school. I don’t hold it against you. It wasn’t you—it was the system that taught you those ways.’”

‘I brought back love, dignity, and honour to my family.’

For Randall, breaking the cycle isn’t just about words—it’s about action.

“I brought back love, dignity, and honour to my family. It wasn’t just for my children; it extended to my nieces and nephews, too. We became a hugging family, always telling each other we love one another,” he said.

Parenting, Randall explained, has been profoundly shaped by the impacts of colonialism.

“Parenting has changed a lot for us because of the impacts of residential schools and the social issues that followed,” he said, gazing at the ocean where his ancestors once paddled their canoes.

The trauma of colonialism, he believes, made his communities more vulnerable to challenges like addiction.

“My parents struggled with alcoholism. When they were sober, they were loving and strong, but alcohol created a lot of chaos,” he shared. “When my father drank, he became violent. He would beat my mother, and as kids, we’d pile on him to protect her.”

Randall’s resolve to break the cycle became clear when, at just 15 or 16, he stood up to his father.

“I told him, ‘You’re not doing this anymore.’ From that moment, I made a promise to myself: I wouldn’t drink, and I wouldn’t act that way with my kids,” he said.

“Carrying an ancestral name means you honour it by not tarnishing it with alcohol or drugs. You show respect by honouring yourself and living in a way that upholds the dignity of the name,” he explained.

“A healthy, happy life leads to healthy, happy children,” he said.

‘Residential Schools took so much from us’

Randall and his family focus on “building a better community by prioritizing education and maintaining zero tolerance for harmful behaviours like drugs and alcohol.”

He believes that rebuilding the connections severed by residential schools is key to healing.

“Residential schools took so much from us—our culture, our language, our connection to the land,” he says.

“Losing those connections created the social ills we face today. Drugs, alcohol, and the resulting tragedies have taken so many lives. If residential schools hadn’t existed, we’d still have our traditions, like puberty rites, which helped guide young people into adulthood.”

But for Randall, the focus is not on what was lost—it’s on what can still be reclaimed.

“It’s about actions,” he says, a smile breaking through.

“The hugs I share with my children and grandchildren, the milestones we celebrate together, and the pride I feel when I hear my granddaughter speak our Squamish language fluently. That’s what healing looks like—choosing love, every single day.”

A mother’s path: Kalkalilh’s story

Kalkalilh, Deanna Lewis is a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw (Squamish Nation) councillor.

Her journey also shares this dedication, but her path has been deeply influenced by her grandfather’s experiences in residential school—a history that continues to shape her parenting and daily life to date.

‘They just called him ‘boy’’

“My grandfather and grandmother both went to residential school,” Deanna begins.

Her grandfather, Norman Lewis, was born on December 25, 1920, the same year the amendments to the Indian Act made attendance compulsory for First Nations children aged seven to 16.

Enforcement of this policy, however, varied across regions and over time.

At age five, he started school, unable to speak English. “For two years, they refused to call him by his native name—they just called him ‘boy,’” she recalls.

Every child was assigned a number, a dehumanizing system that stripped them of their identity.

“That number was on your desk, your bed, and your clothes, and you were responsible for those materials,” Deanna says.

Though she never learned her grandfather’s number, she knows the pain it represented.

Norman’s time in residential school left lasting scars.

“He had to teach himself how to read, write, and do math later in life because he became a logger—a boomer—a very prestigious job at the time,” she says.

But even with his success, the schools taught him neither nurturing nor love.

“He believed being a good parent just meant providing food and shelter.”

This lack of nurturing created a ripple effect, deeply impacting the next generation.

‘She struggles every day with intergenerational trauma’

Deanna’s mother bore the brunt of this emotional absence.

“My mom had a very hard relationship with her father,” Deanna says. Strict rules and emotional distance defined her mother’s upbringing.

Yet, Deanna experienced a different side of her grandfather. “He was kind to me and taught me about our culture,” she shares.

His transformation as an Elder revealed his deep regrets. “He admitted he believed in tough love and that it wasn’t the right way to raise children.”

Though her mother has been sober for 34 years, the trauma persists. “She struggles every day with intergenerational trauma.”

‘Healing is ongoing. It’s a lifelong journey.’

For Deanna, the cycle of trauma stops with her.

“Healing is ongoing,” she says. “It’s not like you go to a camp one day, and everything is better. It’s a lifelong journey.”

She made intentional choices to ensure her children’s upbringing would be different.

“I never had alcohol around my kids when they were young,” she explains.

“I spent years not drinking, especially during their first five years.”

Deanna believes it’s essential to model healthy habits and show her children that they can break cycles of addiction and self-medication.

Her efforts have had a profound impact on her three children.

“When my eldest daughter was about 10 or 11, I told her I wanted her to be better than me,” she recalls.

Her daughter’s response?

“‘Mom, you’re already amazing. That’s a high bar.’”

Now, her daughter leads plant walks at Stanley Park and works as an artist and guide.

Deanna’s son is studying power engineering at the British Columbia Institute of Technology, and her youngest daughter, at just 11 years old, is already demonstrating leadership qualities.

“She could have done the opening for the event we attended this morning,” Deanna proudly shares.

‘We pray together, take river baths, sing our songs’

For Deanna, cultural immersion is integral to raising her children.

“We pray together, take river baths, sing our songs, and perform our dances,” she says.

These practices reinforce their identity and sense of belonging. “My kids know our legends and history because we come from an oral tradition,” she explains.

Deanna emphasizes the importance of “walking in two worlds”—blending modern education with cultural teachings.

“Both are essential tools for life,” she says.

For her, this balance has been lifesaving. “Growing up, I could have easily gone down the wrong path and become a statistic,” she admits.

“But having self-identity is the best gift I can give to anyone in my family or community.”

‘I stand here as a strong Indigenous woman’

Despite the challenges, Deanna honours the strength of her family.

Her grandfather, a Lacrosse Hall of Fame inductee and talented artist, remains a guiding influence. “He taught me our language,” she says.

Yet, his trauma never fully healed.

“He would never have said he was a proud Indigenous person because that pride was beaten out of him.”

Deanna recalls a heartbreaking moment shortly before her grandfather passed.

As she helped him prepare for a lacrosse game, he scrubbed his skin with Dettol, a harsh cleaning product meant for mildew.

When she asked why, he replied, “I’m going to hell for the colour of my skin.”

The nuns at the residential school had told him so as a child.

“It broke my heart,” Deanna says.

“That’s why I do the work I do—because he didn’t have a voice. I stand here as a strong Indigenous woman because my grandparents and my mom never had the opportunity to be proud of who they are.”

“For parenting, I was taught that children mirror what they see,” she says. “Parents are their first teachers.”

She continues, “My eldest daughter, Seraphine, leads plant walks at Stanley Park now. Once, some of my friends and distant cousins went on her tour, and they told me, ‘It sounded just like you talking to us.’ That’s how deeply they’re immersed in our culture.”

By immersing her children in their culture and leading by example, she’s ensuring the next generation can walk confidently in both worlds.

A grandmother’s legacy: Spelex̱ílh’s story

For Spelex̱ílh, also known as Anjanette Dawson, a Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation Knowledge Keeper, this journey is just as personal, but it starts from a place of quiet realization.

“Growing up, I didn’t know what residential schools were,” Anjeanette says, her voice steady but tinged with emotion.

“I didn’t hear the term until I was 15. By then, I already knew something was wrong—what felt normal wasn’t really normal.”

Like Deanna, Anjeanette’s path to healing has been shaped by the long shadow of residential schools

‘Growing up with residential school survivors’

“Growing up with residential school survivors, it’s exactly as you’ve heard,” says Dawson.

“When people say, ‘Get over it,’ they don’t understand what happened to children in those institutions. It explains a lot about how we got to where we are today as Indigenous people.”

Dawson’s parents both attended residential schools.

Her father carried immense trauma from his experiences, while her mother never spoke of hers.

“Looking back as an adult, I’ve realized what felt normal wasn’t actually normal. But it seemed normal because everyone I grew up with had parents who were also residential school survivors,” she says.

‘No hugs, no kisses’

Dawson recalls the lack of affection in her household.

“My parents didn’t know how to show love or affection. There were no hugs, no kisses—nothing like that,” she shares.

She also uncovered unsettling stories about life in residential schools, such as how children were treated for basic needs like oral hygiene.

“Instead of teaching kids how to brush their teeth, they often pulled them out,” she explains. “Some survivors I’ve spoken with haven’t had their own teeth since they were seven or eight years old.”

This lack of basic guidance trickled down to the next generation.

“Parents didn’t teach oral hygiene because they didn’t have teeth themselves. It created this ripple effect, and dentists made a fortune. I remember kids coming in with 10, 12, even 20 cavities because no one taught them how to brush or floss.”

Two parents, two paths

Dawson’s parents emerged from residential schools with starkly different perspectives.

“My mom came out a devout Catholic, while my dad wanted nothing to do with religion,” she says.

Her mother raised Dawson and her siblings with a strict focus on cleanliness—mirroring what she was taught in residential school.

“She brought us up the same way she was raised. The house had to be spotless,” Dawson explains.

Her father, by contrast, was shaped by his own experiences in ways that left him distant. The disconnect between her parents reflected the lasting impact of residential schools on their lives.

Culture and traditional teachings were absent during Dawson’s childhood.

Her parents, raised by nuns and priests, hadn’t been exposed to their own ceremonies, protocols, or language.

Later in life, Dawson's mother sought out cultural mentors.

“She started picking up our traditions in the 1980s and 1990s,” Dawson says. “But by then, I had moved away from home for 12 years, so I didn’t see her reclaiming our culture firsthand.”

When Dawson returned home to be with her mother in her final years, she saw glimpses of that transformation.

“She wanted to learn more, but it was too late in her life to fully embrace it. She picked up a few words here and there, but nothing substantial was passed down or shared with her,” Dawson says.

Like her mother, Dawson found herself seeking out knowledge on her own.

‘Culture saved my life’

“Culture saved my life,” Dawson says with quiet conviction.

Her commitment to reclaiming her identity as an Indigenous woman has not only been transformative for her but also for her children and grandchildren.

“For me, my ‘religion’ is my culture. That’s where I come from, and that’s how I’ve raised my kids—and probably how I’ll raise my grandchildren too,” she says.

Dawson ensures her children have access to cultural teachings but doesn’t force them to participate.

“If they want to attend ceremonies or learn, that’s their choice. But I support them fully and connect them with cultural people in my life who can guide them,” she says.

‘I make intentional choices to parent differently’

For Dawson, parenting is about consciously breaking cycles.

“I’ve worked hard to be aware of the patterns that came from my parents’ trauma,” she says. “I make intentional choices to parent differently.”

One of her core principles is fostering open communication.

“I give my kids and grandkids the freedom to express their feelings, something I didn’t have growing up,” she shares. “I want them to know they have a voice, and they should use it.”

Dawson also ensures her children grow up in a safe, supportive environment free from the harmful behaviours she experienced as a child.

“My husband and I committed to no drinking, no drugs, no smoking. Children learn by what they see and hear, so we wanted to create a healthy home.”

This intentionality extends to her work supporting other families as an educator and mentor.

“In my role, I help parents understand that some of the patterns they’re perpetuating aren’t normal—they’re the result of residential school trauma,” she says.

“It’s about teaching them that healing is possible, even if it feels like starting from scratch.”

‘Breaking cycles takes time’

Dawson’s commitment to breaking cycles and reclaiming culture is as much about the future as it is about healing the past.

“When I had my own children, I became more aware of the trauma I’d experienced and knew I didn’t want them to go through the same,” she says.

For her, parenting isn’t about perfection—it’s about progress.

“There are moments when you wonder if you’re doing enough, or if you’re inadvertently passing something down,” she says.

“But breaking cycles takes time. It’s about healing together as a family and creating a safe space for future generations.”

Between 1870 and 1996, more than 150,000 Indigenous children were taken from their families and placed in residential schools.

If this story was triggering, The Indian Residential School Survivors Society operates a 24-hour crisis line to support survivors and families across British Columbia and beyond. Call: 1 (800) 721-0066

Correction: Please note that the story was corrected since first posted to correctly spell Anjeanette Dawson's name.

Bhagyashree Chatterjee is The Squamish Chief’s Indigenous and civic affairs reporter. This reporting beat is made possible by the Local Journalism Initiative.