As sculptor Jack Gibson prepares for this weekend’s Art Crawl — during which 169 Sunshine Coast galleries and studios will open to the public — the creative fire of the Garden Bay-area artist is stoked by a simple vision of cross-cultural collaboration.

“What does reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous artists look like? Just doing good work and building relationships,” Gibsons said. “Working together in harmony and appreciating each other’s work.”

Gibsons is a self-taught artist who specializes in finely-wrought human and animal sculptures. He carves figures in wax before they are cast in bronze, after which he applies a russet patina.

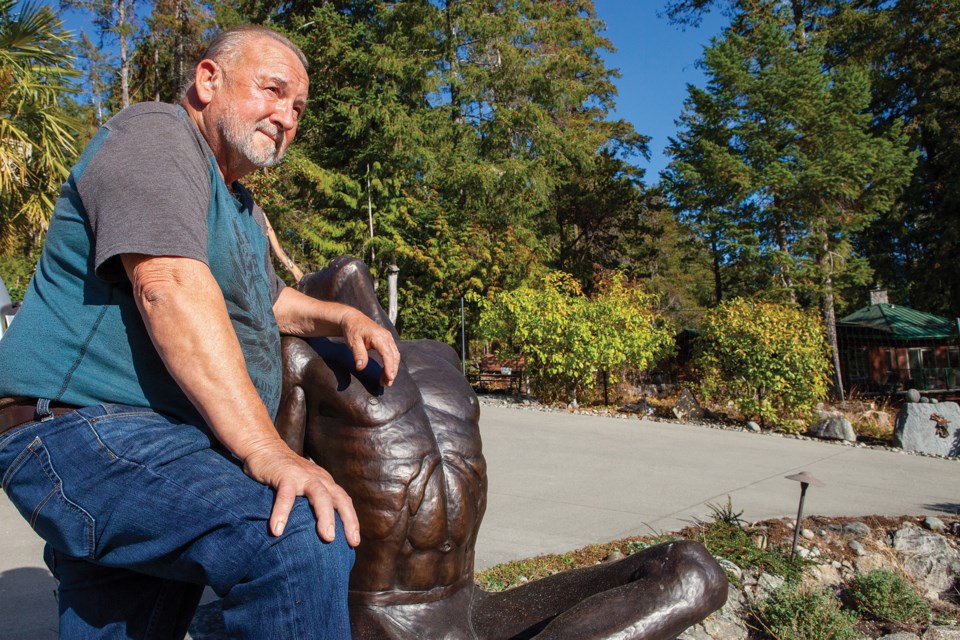

His life-sized sculpture Yonel, of a seated male dancer whose rigid musculature and rapturous physiognomy belie its metallic surface, is positioned steps from Gibson’s home-based studio and gallery.

Other figures punctuate the hillside grounds. Gibson himself landscaped the property and designed his house, whose shape evokes an eagle with outstretched wings. Gibson and his wife moved to Garden Bay in 2009.

Yonel was modeled on a former Cuban navy SEAL turned contemporary dancer. During a trip to Cuba in the late 1990s, Gibson was inspired by the challenge of translating dancers’ lithe movements into three-dimensional moments frozen in time. It was an unexpected direction for an artist who had previously crossed the Arctic circle to capture moving images that became casts of goats (Big Billy), moose (Dom), eagles (Regal) and other untamed creatures.

The Cuban trip was meant as respite from the stress of operating two Vancouver art galleries and representing more than 40 visual artists. (Gibson still promotes artists and will feature Yukon landscape painter Emma Barr as a guest artist during the Art Crawl.)

Cuba opened a whole new chapter in Gibson’s creative career. In addition to launching his intricate depiction of dancers, he cultivated expertise in creating cold-cast bas relief panels. In Kings’ Prey, a series of 220 polymer resin tiles, bodies of Chinook and Coho salmon connect across edges, forming an Escher-like undersea cavalcade.

Gibson has been sought out by Indigenous carvers like renowned Musqueam artist Susan Point to create molds and casts of their designs for limited release in metal or marble.

The late Haida artist Ben Davidson engaged Gibson to render his shield-shaped artwork Raven Clam People in composite metal.

Gibson also undertook a detailed study of Kwakiutl and Kwakwakawakw Nation dancers which resulted in his series of sculptures depicting ceremonial regalia and poses.

“I used to carve in stone,” Gibson said, “but the thing about stone is that it’s forgiving. Nobody expects it to be anatomically correct. The minute you move into clay or wax, you become dedicated to detail. I keep trying to go abstract, but [precision and realism] keep coming back, haunting me all the time. So I guess I’m stuck with it now at my age.”

The lissom fingers and taut sinews in his bronze Bukwas, which depicts the Kwagiulth Nation’s mythological Wild Man of the Woods, echo the meticulousness of Gibson’s graceful nudes like Serene, in which a female rests in a fetal position.

“Sometimes you don’t even need lips or eyes on a piece,” Gibsons said. “You get everything you need to feel from the body.”

Gibson maintains a website at jackgibsongallery.com. His studio and gallery will be open during the Art Crawl as Venue #158.