In a season whose carols extol seraphic skies, local astronomers are taking steps to keep the stars shimmering year-round. Leaders of the Sunshine Coast Astronomy Club — officially, a “centre” of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada — are talking up the benefits of darker skies in Sechelt.

“Two-thirds of the world’s population can’t see the sky,” said Charles Ennis, the astronomy club’s president and a former police dispatcher. Ennis is armed with examples of urban light sprawl that blinds motorists, obscures hazards, and occludes a clear view of the constellations.

“Cities are lighting up the universe,” he added. “They’re wasting a huge amount of money doing that. There’s no reason for it, because we’re daytime animals. Scientists have determined that [excess urban light] is possibly a carcinogen, because it interferes with people’s sleep patterns. No one’s bedroom is ever dark.”

Ennis cited research defying conventional wisdom that brighter lighting reduces crime. In 2014, Summerland researcher (and national science fair scholarship-winner) Grant Mansiere crunched RCMP data to show that more intelligent street lighting is connected to reduced rates of criminal activity. “[In] the city of Calgary,” Mansiere announced, “they cut the wattage in half in all 17 districts and 15 showed reduced crime with reduced wattage.”

Ennis has shared his presentation with neighbourhood associations across the Sunshine Coast. The response has been enthusiastic, he said, because reduced and directional nighttime illuminations have a tangible benefit: lower electricity costs. Doubts about nighttime safety are dimmed by a visual object lesson: a police cruiser’s “wall of light” that mollifies drivers at nighttime traffic stops. In that case, overwhelming beams help ensure an officer’s safety. Elsewhere, though, similarly blinding street lights can make suspicious activity disappear amid harsh shadows, flares and halos.

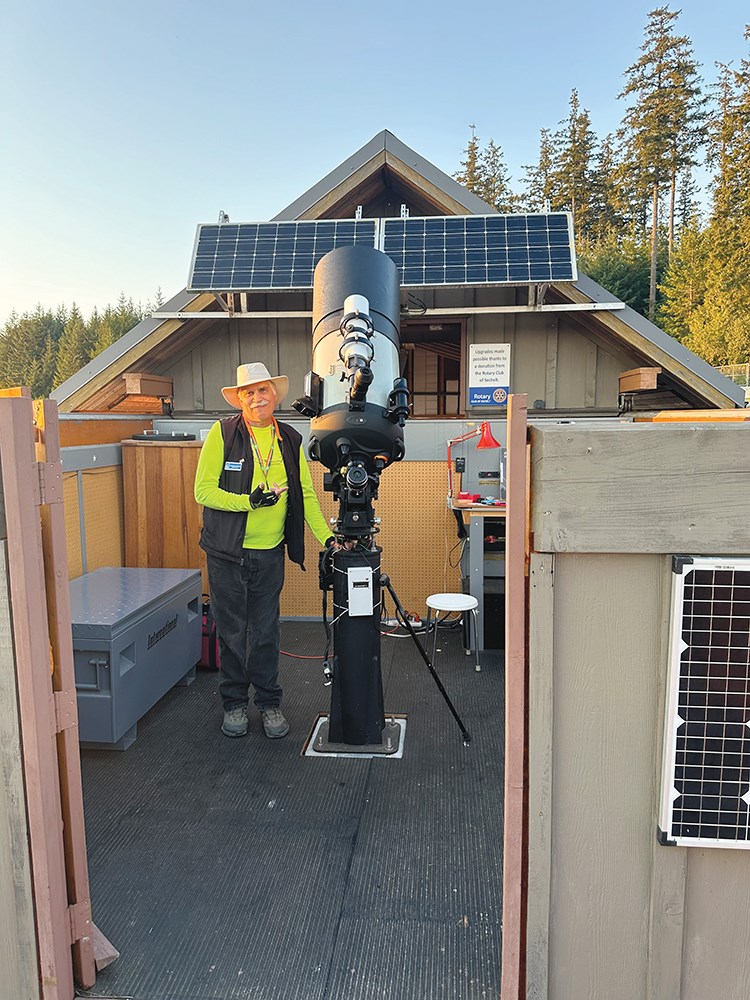

The benefits for local stargazers are clear. The astronomy club’s observatory is located above Field Road in Wilson Creek. 24-hour flood lighting from the Heidelberg Materials mine site has gradually been encroaching on the group’s telescope use. “I asked them, do you work 24 hours a day?” recounted Ennis. “If you’re not mining all night, why are you lighting the world?” Dialogue with Heidelberg officials is ongoing, building on the company’s earlier mitigation of incandescent lighting for its conveyer system.

At a recent planning meeting of regional tourism strategists, Ennis and his wife Laurel (herself a prolific astrophotographer) extolled the virtues of dark skies. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada maintains three designations for dark-sky sites. If the Sunshine Coast (or parts of it) qualified as an Urban Star Park, it would mean controlling artificial lighting with strict and active measures while educating and promoting the reduction of light pollution to the public and nearby municipalities. Such skies are generally brighter than so-called dark-sky preserves and nocturnal preserves, but are still usable for astronomy.

The potential for “dark season” visitors — with an affinity for astronomy — gradually dawned on the tourism planners. In Jasper National Park, an annual Dark Sky Festival has been attracting stargazers for 15 years.

Ennis and the astronomy club are concentrating their initial efforts on the District of Sechelt, with an information campaign due to turn up the intensity in 2025. “I know that if we can get them to go for it, it’s going to be like dominoes,” he said. “Everyone else will want to be part of it.”