Hardcore readers of these monthly meanderings (there may be a few of you) will likely notice the similarities to the December 2023 article. Yes, it’s come to this, mainly because we’ve come around to the same part of our orbit as last year. Jupiter will be at opposition to the sun Dec. 7 and is a little farther east than last year. One object that wasn’t there last year is Mars; it passed Jupiter going from west to east against the stars on Aug. 14 of this year and was about one-third of a degree north of Jupiter as it passed – less than the width of the moon.

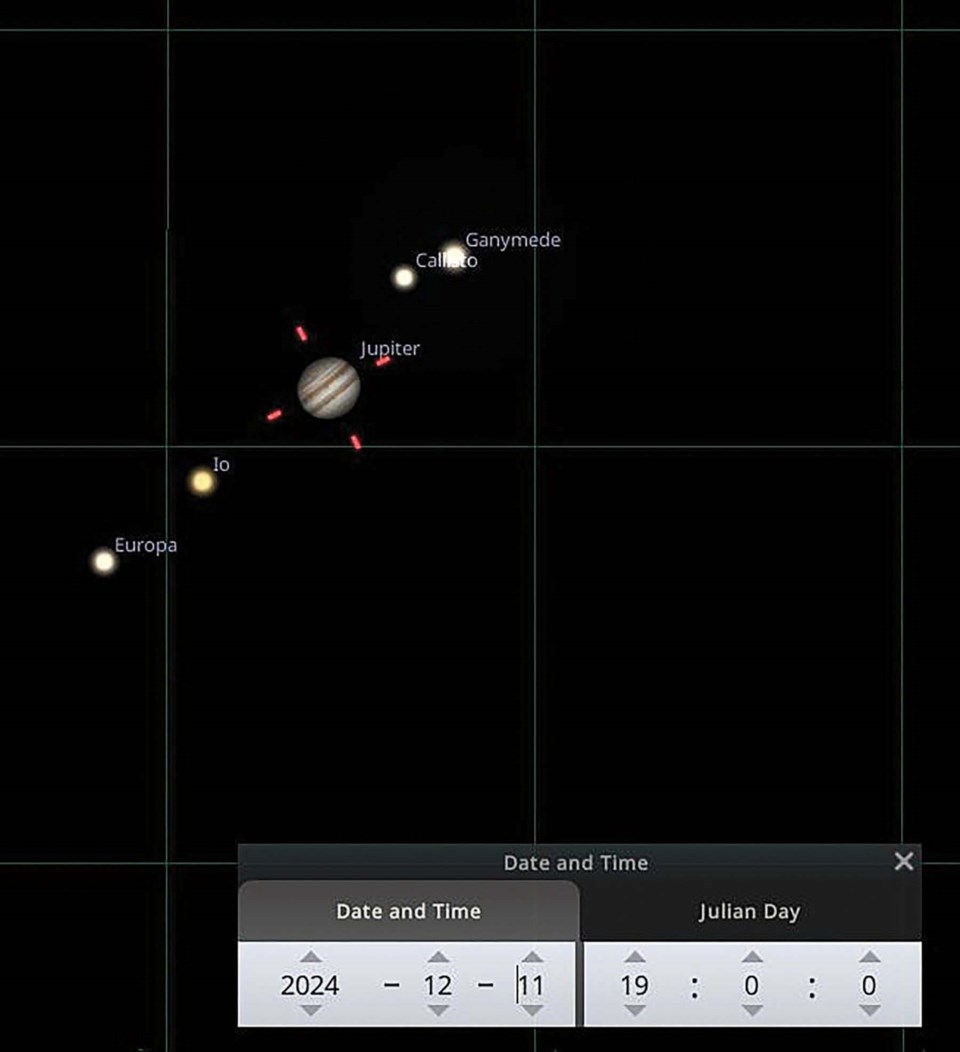

Jupiter is as big and bright and close as it gets, visible basically all night. A stable pair of binoculars or a small telescope is enough to allow you to see its four big moons, known as the Galilean moons: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. The cheaper solution: download Stellarium, set your location and, after a bit of learning the controls, prepare to watch the moons orbit and swing back and forth around Jupiter. Astute observers will also notice that Jupiter is also moving backwards against the stars in December – retrograde motion – from east to west. Its motion doesn’t really reverse, of course, it just looks like it because of parallax and our own more rapid orbital speed around the sun.

The Geminid meteor shower occurs every December, reaching its predicted peak Dec. 13/14. The moon will be almost full though, which will wash out many of the meteors this time. The radiant will be beside the bright star Castor in Gemini (left and above Orion) and will be above the horizon all night. Jupiter, Aldebaran in Taurus and the moon will form a triangle to the right of the Geminids radiant point. The Geminid shower is one of the more populous we see with a Zenithal Hourly Rate of 120, for example. The typical meteors are white and bright and not particularly fast, compared to Perseids or Leonids. For some interesting info on other notable meteor showers (or ‘storms’) check out: space.com/greatest-meteor-storms-in-history. As with all showers, just find a warm comfortable place to lie down under an open sky and look up. While the meteors will appear to radiate from Castor they can appear anywhere in the sky.

The Geminids also have an unusual source; rather than a comet, it seems to be the asteroid 3200 Phaethon. This has a highly elliptical orbit with a perihelion of only 13 million miles from the sun (inside Mercury) and an aphelion of 222 million miles (out past Mars). I mentioned last year the source of the dust and solids is likely from thermal effects of close passes to the sun, but I recently read one source that spoke of the possibility of a collision in its past. The solar wind and light pressure along with gravitational effects would certainly spread out any associated cloud of dust and debris.

Earlier articles mentioned Mars’ appearance in the evenings. Coincidentally, when Jupiter reaches opposition (to the sun) on Dec. 7, Mars also reaches its first stationary point and begins to appear to move east to west (retrograde) until its own opposition on Jan. 15. This won’t be a very good opposition of Mars since it will be near its aphelion (farthest from the sun) and will reach magnitude -1.4 and span about 14.5 arcseconds. July 2018 was much better at -2.8 and 24.2 arcseconds, simply because Mars has a definitely elliptical orbit and it was almost at perihelion (closest to the sun) that month.

The International Space Station ends its evening passes on Dec. 5, takes a week off and resumes with morning passes on Dec.13 that continue through the month.