Early one Greek morning, Theo our taxi driver whisks us to the Palace of Knossos, just outside Heraklion. Cicadas chirp and peacocks call plaintively from cypress trees welcoming us to the fabled palace of powerful King Minos.

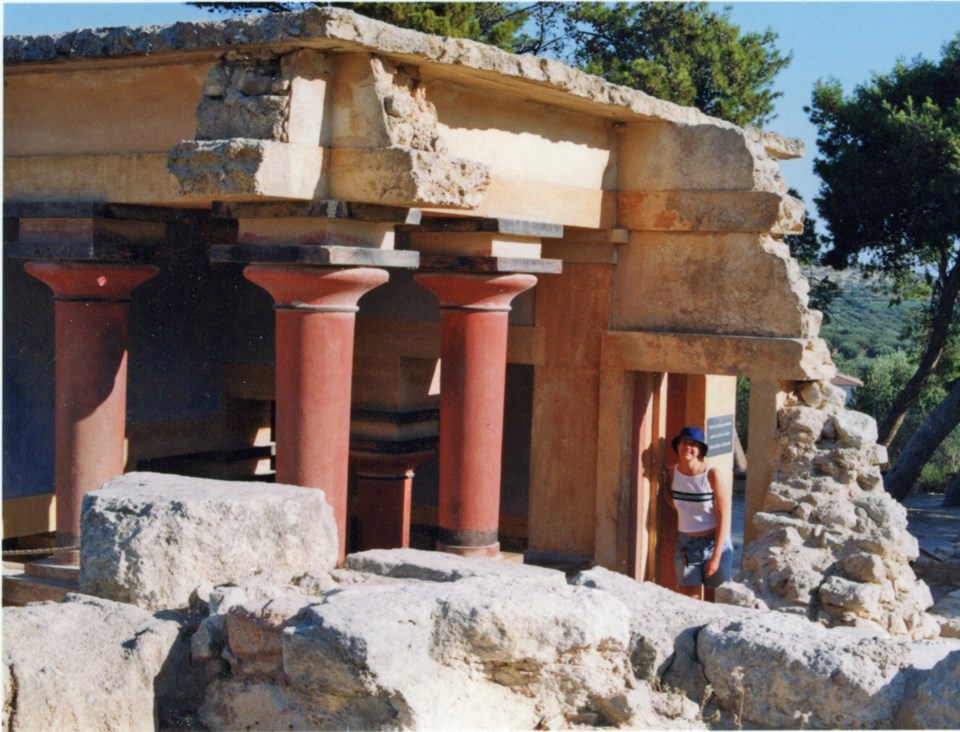

Above the entrance, three thick red columns support a restored flat roof. Placards recount that in the early 1900s, British archeologist Sir Arthur Evans had systematically excavated these arid foothills below Mount Ioukt. In reconstructing this royal Minoan city, he discovered a labyrinth of rooms embellished with frescos of bulls. I recall how the myth of a ferocious half-man, half-bull living in the palace fascinated my students years ago.

The walkway parallels remains of stone-paved Royal Road, built by Minoans over 1,000 years before the Romans. Carts transported fine pottery and silver crafts along here to the now distant harbour. There, sturdy, square-sailed ships manned by brawny oarsmen made Knossos a maritime power.

Opposite the palace, rows of stone seats at the amphitheatre prompt images of Minoans attending acrobatic performances staged on the platform below.

Inside the palace, Hall of the Double Axes, we imagine King Minos pondering big decisions – like how to quell offshore pirates. And in the central courtyard, charred 1350 BC storage jars testify to an ancient fire. Plaques explain that today most of the excavated original statuary, pottery, wall paintings, sarcophagi and papyrus manuscripts reside in Heraklion’s Archaeological Museum.

In the adjacent King’s Chamber, a lustrous alabaster throne stands amid paintings of griffins and lilies. Through a narrow passageway into the Queen’s apartments, we see murals of dolphins and spirals. Fragmented, brightly coloured figures of men and women convey sophisticated lifestyles, ceremonies, games and religious festivals. The most famous depicts a young man somersaulting over a huge bull.

The Queen’s bathroom features flush toilets and terracotta bathtubs, more practical luxuries. And carrying hot and cold water, pipes provided heated floors. Drainage pipes flushed wastewater into outer gardens.

From outside the palace grounds, Theo takes us to the Venetian Wall, surrounding Heraklion’s old city since 1462. There, Nikos Kazantzakis, Crete’s greatest modern writer, is memorialized atop Martinenga Bastion. Popular movies were based on Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ, two of his many contentious novels. We remember worldwide protests at their screening.

“Excommunicated for questioning Christian beliefs, our Bishop refused to bury Nikos when he died in 1957. His casket lay at the Saint Minas steps for days,” Theo tells us. “Demanding suitable burial for our hero, officials eventually arranged this special place.” The epitaph taken from his work proves poignant: “I hope for nothing; I fear nothing; I am free.” Surrounded by crimson bougainvillea, Kazantzakis perpetually surveys his beloved homeland.

We walk down to beautiful Saint Minas Greek Orthodox Cathedral below, relatively young at 150 years old. Amid olive trees shading the plaza, worshippers chat with each other and buy little white candles before entering its massive carved-wood doors. Inside, gold and silver chandeliers illuminate frescos, sacred icons and statuary.

Sipping cold juice in shimmering 29-degree heat, we head to the central market. Mingling with locals, we browse stalls piled high with produce, clothing and handicrafts. Fresh fish glisten on beds of crushed ice. Scrawny chickens twirl overhead on braided strings. And as tradition dictates, we haggle for packets of dusty-green, rusty-red and brilliant-yellow seasonings perfect for spicing up home meals.

Typical of Greek ports, blue chairs and tables sit outside tavernas. Spirited bouzouki music bursts from doorways. Small fishing boats bob inside the harbour. And boisterous seagulls march along the jetty.

With faces cooled by ocean breezes, we reboard our ship carrying glorious memories.

See www.vikingcruiseline.com Antiquities of the Mediterranean for more.