A B.C. infectious disease institute is teaching renters and seniors how to build hundreds of homemade air filters inspired by a design first developed during the COVID-19 pandemic — only instead of capturing airborne droplets, the goal is to clean people’s apartments of wildfire smoke.

Last year, a group led by Simon Fraser University’s Pacific Institute on Pathogens, Pandemics and Society taught residents across Metro Vancouver how to build 500 air filters to reduce exposure to fine particulate matter from wildfires. Also known as PM2.5 for its 2.5 micrometer diameter, fine particulates can trigger lung cancer and chronic pulmonary disease, while making asthma and existing lung illnesses much worse.

“There's many people who are stuck in places where they don't have air conditioning, they have to open windows, then that lets the smoke in. And now what?” said Anne-Marie Nicol, an associate professor of professional practice in SFU’s Faculty of Health Sciences.

“We're trying to meet people where they're at to tell them how they can help themselves.”

The group hopes to exceed the number of air filters produced last year by taking the workshops on the road. They plan to target seniors, people with pre-existing health conditions and renters who might not be able to afford commercial air filters.

In addition to dozens of workshops in places like Vancouver, the North Shore and New Westminster, this year, Nicol says they are expanding into the Fraser Valley and Interior. This week, they will run training in Abbotsford and Chilliwack, and next week, they’re heading to Kelowna, Summerland and Oliver.

Nicol says they are working through municipalities or community groups to identify and recruit people who need the free workshops most. One barrier is funding, something that so far has kept her from expanding into often smoky places like the Cowichan Valley on Vancouver Island.

“This started as a research project. Now, I see there’s a real need,” Nicol said.

Pandemic inspiration picked up for wildfire smoke

That DIY inspiration revolves around a set of devices known as Corsi-Rosenthal boxes. Jim Rosenthal, CEO of Tex-Air Filters and co-inventor of the device, came up with the design with Richard Corsi, a friend of 20 years and engineering professor at the University of California Davis.

“In 2020, my world was 'How can I help?'” said Rosenthal.

Rosenthal's company first chipped in through the manufacturing of 30,000 masks for hospital workers. Then Rosenthal and Corsi got a call from a reporter who asked them about cleaning indoor air by placing a filter behind a fan.

Rosenthal said he tested out several 20-by-20 filters on a box fan and found out it worked “pretty well.” Corsi then suggested “Well, what would happen if you made a box?” Rosenthal came up with a device using four filters taped together with a box fan on top. More filter surface area gave it more power to clean a larger room, Rosenthal explained in an interview.

“The idea was to create something that was inexpensive that anybody could built at home. We were thinking about schools, underserved communities, homeless shelters, churches, anywhere where you can use a good air cleaner and do it for a really low cost,” said Rosenthal.

“It is incredibly effective. Much more so than we ever thought.”

The filter design blew up across social media, and garnered attention from media across the world. That was the first wave of interest. The second, said Rosenthal, came in the summer of 2023, when Canada’s most destructive wildfire season on record sent massive quantities of smoke across the country, flooding cities on both sides of the Canada-U.S. border and even reaching as far as Europe.

As outdoor air particle counts went “off the charts” in New York, Massachusetts and Ohio, Rosenthal said he became a cheerleader for indoor air quality.

“People are putting new things out there. And they're saying how did I do? It's my job to say well, you did great. Make your shroud a little bit smaller, a little bit bigger, or you need a shroud or, you know, that's a really good idea. It's beautiful,” he said.

“It became everybody's project.”

A $100 effective solution to smoky air

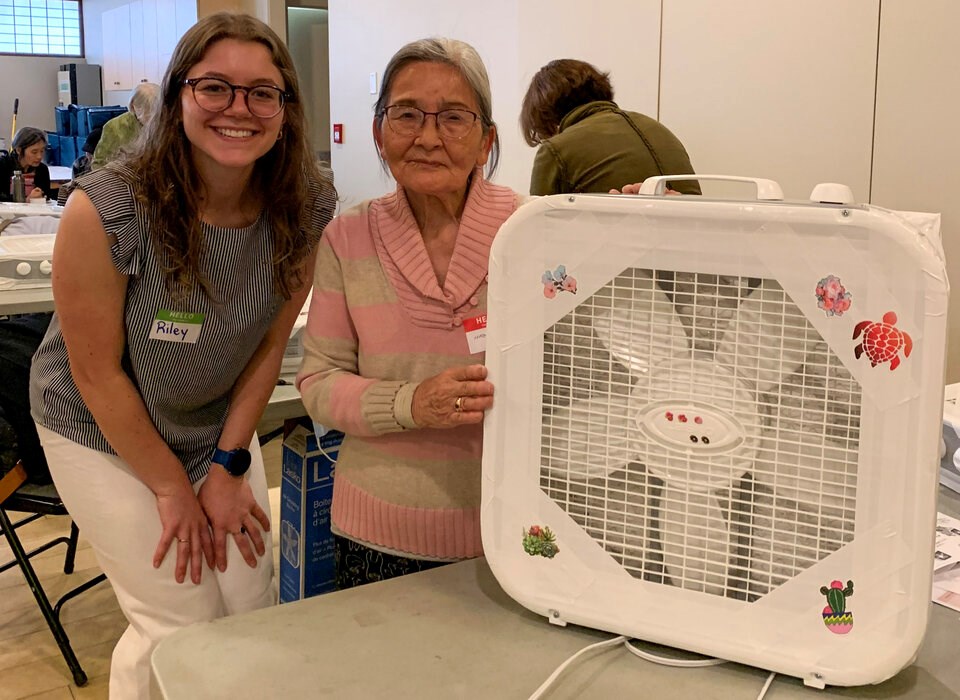

Nicol said she’s wants to bring that kind of community enthusiasm to B.C. In its simplest version, workshop participants are guided through how to tape a 20-by-20-inch air filter to a box fan. Tape added to the front of the fan creates a shroud to focus incoming air into the filter.

Anyone who can’t make it to a workshop but still wants to make a filter can pick up a free guide and the materials — a box fan, a MERV-13 furnace air filter and roll of white duct tape — for less than $100.

For less than half the price, the DIY device operates a clean air delivery rate equal to or better than a $250 commercial air filter device, according to studies from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and Canada's National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health.

Nicol said multiple units can tackle even larger rooms. The results, she said, can be both educational and oddly satisfying.

“I have one from last year and it's black on the back,” Nicol said. “You're looking at what's being drawn out of your air and what was gonna go into your lungs.”

With the box design offering more filter surface area and a much higher airflow, Rosenthal said he hopes the next push will be to get larger versions into school classrooms across North America. In the meantime, he said if someone has problems breathing at night because of wildfire smoke, they shouldn't hesitate to go to the hardware store and buy a 20-by-20 filter and a box fan.

“All you’re doing is moving indoor air through a filter. So however you do it is OK,” he said.

“We’ve got this wildfire smoke or COVID or whatever, and we are not helpless. We can do something.”