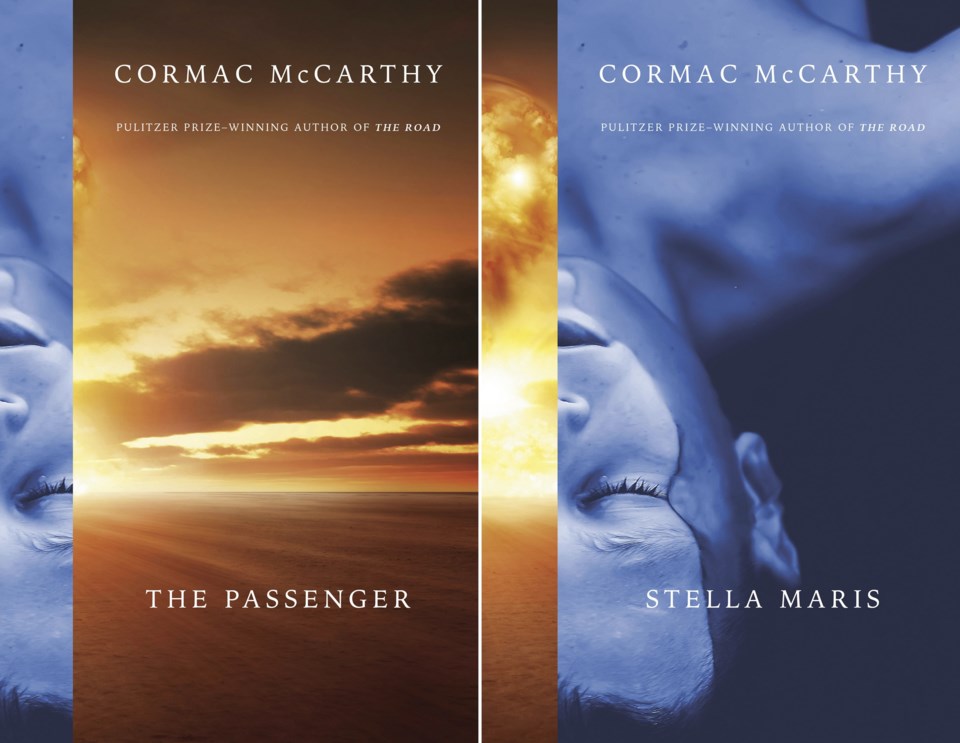

“The Passenger” by Cormac McCarthy (Alfred A. Knopf)

It’s been 16 years since Cormac McCarthy released “The Road” and won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction, cementing his reputation as a master American novelist. Plenty of time, then, to write two books for fans to savor in 2022.

The first, “The Passenger,” is out now, and while it has that traditional McCarthy style (spare prose, few commas and adjectives, scant apostrophes, and no quotation marks to tell you who’s talking), it is nothing if not original. It’s difficult to summarize the plot, but the protagonist is a guy with a great name, Bobby Western. The novel begins in Mississippi in 1980 as Bobby, working as a salvage diver, sits on a Coast Guard boat about to explore the wreckage of a plane crash below the surface. We learn there’s a passenger from the manifest whose body is not on board and the black box is missing. But this is definitely not a mystery novel. If you turn the pages hoping for answers, you won’t find them.

What you will find are deep discussions about quantum mechanics, God, the atomic bomb, who killed JFK, and of course, love. We learn Bobby’s younger sister, Alicia, was a child mathematics prodigy, who while studying for her doctorate at the University of Chicago years ago, committed herself to a mental hospital named Stella Maris in Wisconsin before killing herself. (“Stella Maris” is also the name of the companion novel to be published on Dec. 6.) We learn their father and mother both worked on the Manhattan Project, Dad as one of the scientists with Oppenheimer as they watched the first mushroom cloud fill the sky in the New Mexico desert. Oh, and we learn the siblings loved each other. Incestuously? Unclear. But it certainly haunts them both. Alicia is a diagnosed schizophrenic, visited by various “chimeras.” She dubs the ringleader the “Thalidomide Kid.” He’s small in stature and with flippers instead of hands. She merits her own chapters, all in italics, during which she converses with those hallucinations.

If that all sounds like a lot, you’re right. This is not an easy beach read. It’s difficult to follow at times, in part because the secondary characters are barely introduced. Someone is looking for Bobby — because of the plane crash? Because of his parentage? — and he avoids detection by wandering through the South talking philosophy and cars and nuclear annihilation with people from his past and present as we stitch together his story. Reading “Stella Maris” later this year will help some. Taking the form of transcripts between Alicia and her doctor, it’s formatted as a series of interviews with the patient, set eight years before the events of “The Passenger.” But Alicia is not just any patient. Like her brother, she thinks deeply about everything and shares it all with Dr. Robert Cohen. The only thing she won’t delve into too deeply? Bobby.

At 89, McCarthy still has plenty to say. Both these books ruminate on consciousness, what it truly means to be alive, and whether there are universal truths that govern the world. And while it’s fair to not expect answers to questions so big, some readers will wonder why the stories have to be so cryptic.

Rob Merrill, The Associated Press