From electric skateboards to stand-up e-scooters, British Columbians are transforming the way they get around cities and towns. But there is almost no data to help planners decide what should and shouldn’t be allowed to share paths with pedestrians and conventional bicycles.

That is — until now.

In the first large-scale, real-world study of its kind, researchers from the University of British Columbia working out of TransLink’s New Mobility Lab have found almost all electric-assist vehicles can safely and comfortably co-exist with pedestrians and cyclists.

“They're commercially available and we're starting to see them appear in cities all around the world,” said Alexander Bigazzi, a professor in the University of British Columbia’s School of Community and Regional Planning and head of the Research on Active Transportation Lab.

“But most of these things are illegal. There's no enforcement. Even on the sales side — the shops selling devices technically are illegal to operate on the street.”

Together with researcher Amir Hassanpour, Bigazzi set out to measure just how many of these electric-assist devices are out there and how they are changing Metro Vancouver’s multi-use paths and on-street cycling lanes.

To do that, Bigazzi and Hassanpour set up 12 observation stations across the region in places like downtown Vancouver, the North Shore, Burnaby, Richmond, New Westminster and Surrey.

On the ground, they laid pneumatic tubes across the road to measure the number and speed of vehicles. At the same time, GoPro cameras captured just what kind of vehicles were passing by.

In the end, the two recorded and manually classified over 25,000 vehicles by reviewing the video — what Bigazzi describes as “a lot of work” and one reason why the data doesn’t already exist.

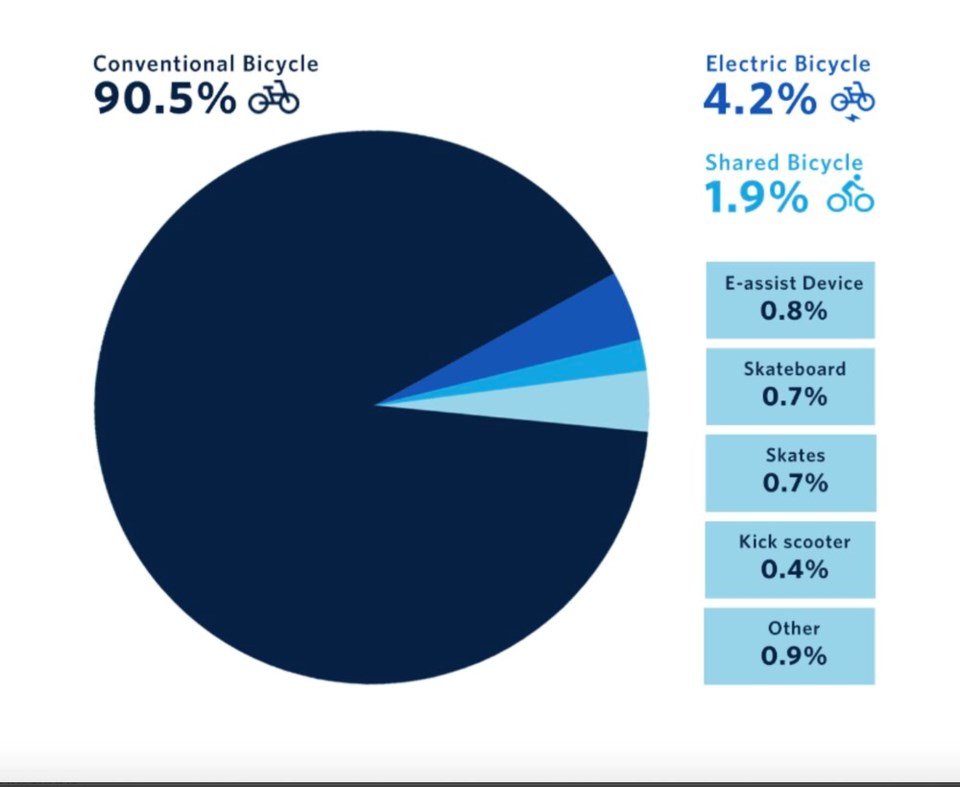

Despite a boom in the electric-assist vehicles, they found a little over 90 per cent of vehicle trips on multi-use paths were still made on traditional bicycles; 4.2 per cent of the trips were made on electric bicycles; whereas only 0.8 per cent were on some kind of e-assist device.

With the COVID-19 pandemic underway, the researchers posted QR codes at the observation stations, calling on people to take part in an online survey that would gauge how comfortable path users were sharing the space with the new vehicles.

Roughly 1,100 people responded.

“Generally, folks are comfortable with the micro-mobility devices,” said Hassanpour.

But when it came to how people perceived the speed of other electric-assist devices, a skewed sense of reality emerged.

“These non-conventional bicycles are much rarer than people think. So they kind of show up in people's memories a lot more than they realize. And probably more importantly, they're not going as fast as people think they are,” said Bigazzi.

Survey respondents tended to gauge the speeds of conventional bicycles within one or two kilometres per hour of the actual speed. But when it came to electric-assist vehicles, they thought they were going twice as fast as they really were.

Almost all the vehicles stayed below the 32 km/h provincial speed limit for electric-assist bicycles — something the researchers say appears appropriate for new vehicles.

But while a very small amount overall exceeded the provincial speed limit, there was one exception: one-third of sit-down, moped-style scooters broke the speed limit and some were found reaching speeds up to 45 kilometres per hour, nearly the urban speed limit for motor vehicles.

“[They're] just really fast and also very uncomfortable for folks to share a path with,” Hassanpour added.

Outside sit-down e-scooters, the largest cognitive bias on electric-assist vehicles comes from something known as “frequency illusion,” where unusual experiences take on outsized places in an individual’s memory, said Hassanpour.

The phenomenon means that any conversation around an e-bike could trigger a memory of that time someone seemed to pass you at high speed going up a hill.

“It sort of leads you to believe that they are more common than they actually are,” said Hassanpour.

The same goes for speed — you remember the fast bicycles more than you remember the average or slowly moving e-bikes.

Bigazzi says their data offers some important insights into how B.C. municipalities should regulate e-assist vehicles going forward.

The most obvious: the province should ban sit-down e-scooters from multi-use and bike paths.

On the other hand, he says, “we should look at allowing a wider range of devices, which requires some legal changes.”

Electric-assist vehicles also have implications for when city planners should consider separating bike and pedestrian paths — the more e-assist vehicles on the path, the lower that threshold should be, so most people feel comfortable.

“The takeaway is that more paths should be separated,” said Bigazzi.

Interestingly, e-assist vehicles were also found to have a traffic calming effect. When mixed with traditional bicycles, they were found to lower the rate of fast-passing events, and even out overall speeds to around 22 km/h.

“There's a potential safety benefit because there'll be fewer overtaking events, and there'll be smaller speed differentials when there is overtaking because people will be going closer to this kind of central 20 to 22 km/h range,” said Bigazzi.

What happens when electric-assist vehicles leave the path and move onto a road shared with cars?

Due to similar speeds, manoeuvrability and equivalent vulnerability to traffic, Bigazzi suspects they could manage road traffic as well as any traditional bicycle.

But he stopped short of recommending government legalize electric-assist vehicles on the road — at least beyond e-bikes, which are already legal in the province, and an e-scooter pilot program in place across several B.C. municipalities.

First, he said, more work needs to be done analyzing the new vehicles’ stopping distance.

“There's a lot of potential for electric-assist mobility to advance our broader goals around sustainability, climate change, public health, reduced traffic, reduced travel costs,” said Bigazzi. “There are some real big potential benefits.

“This is about how can we integrate them.”